There are three types of menswear books. The first are academic or academic-adjacent texts that explore subjects such as the cultural history of hats or the intersection of gender and dress. The second are practical guides to dressing, which, while potentially useful for beginners, are often less engaging once you know the basics. The third are what I call “picture books,” where you buy something more for the pictures than the prose. In an age where so much style inspiration lives online, these titles offer diminishing value, especially since many recycle the same photos of Steve McQueen and Cary Grant.

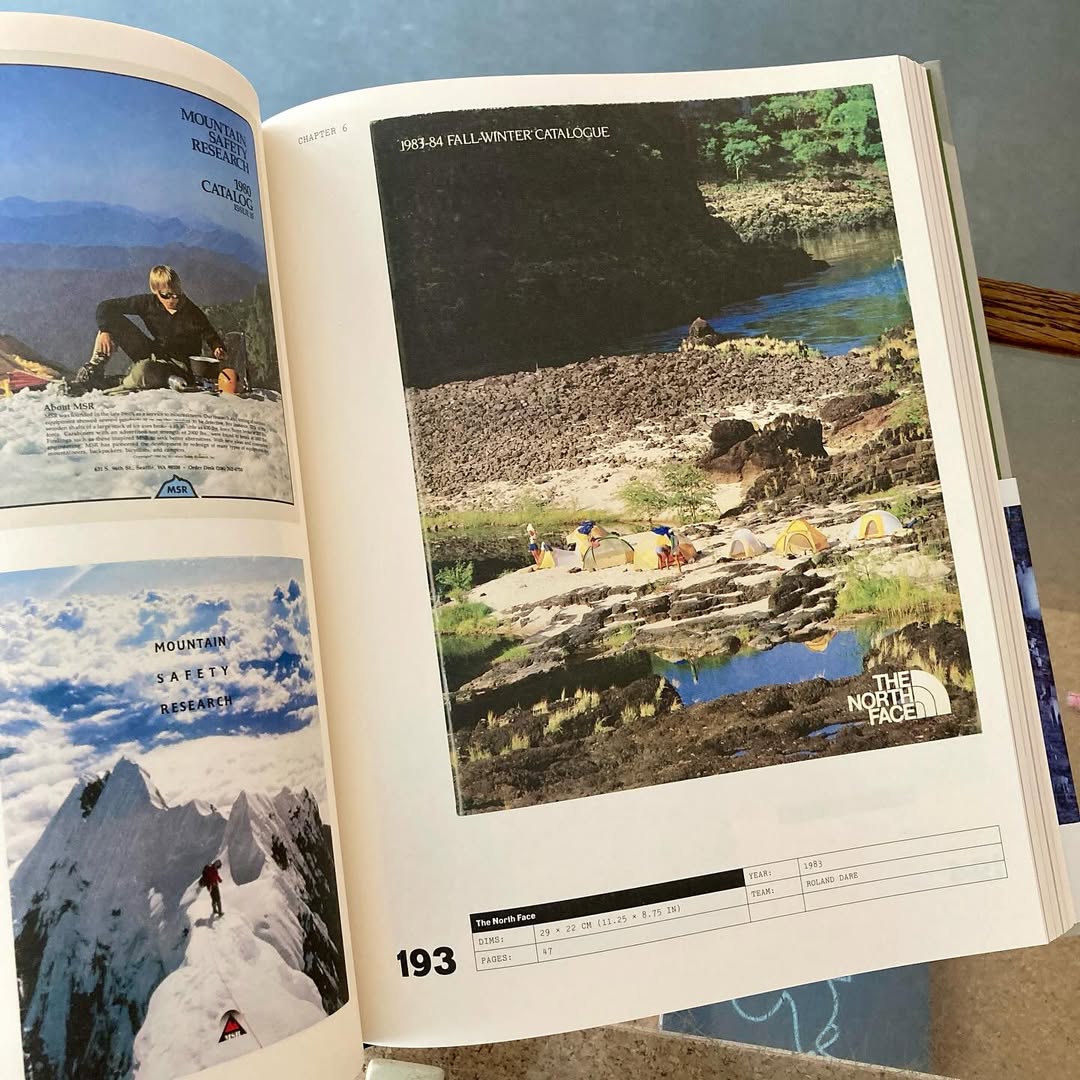

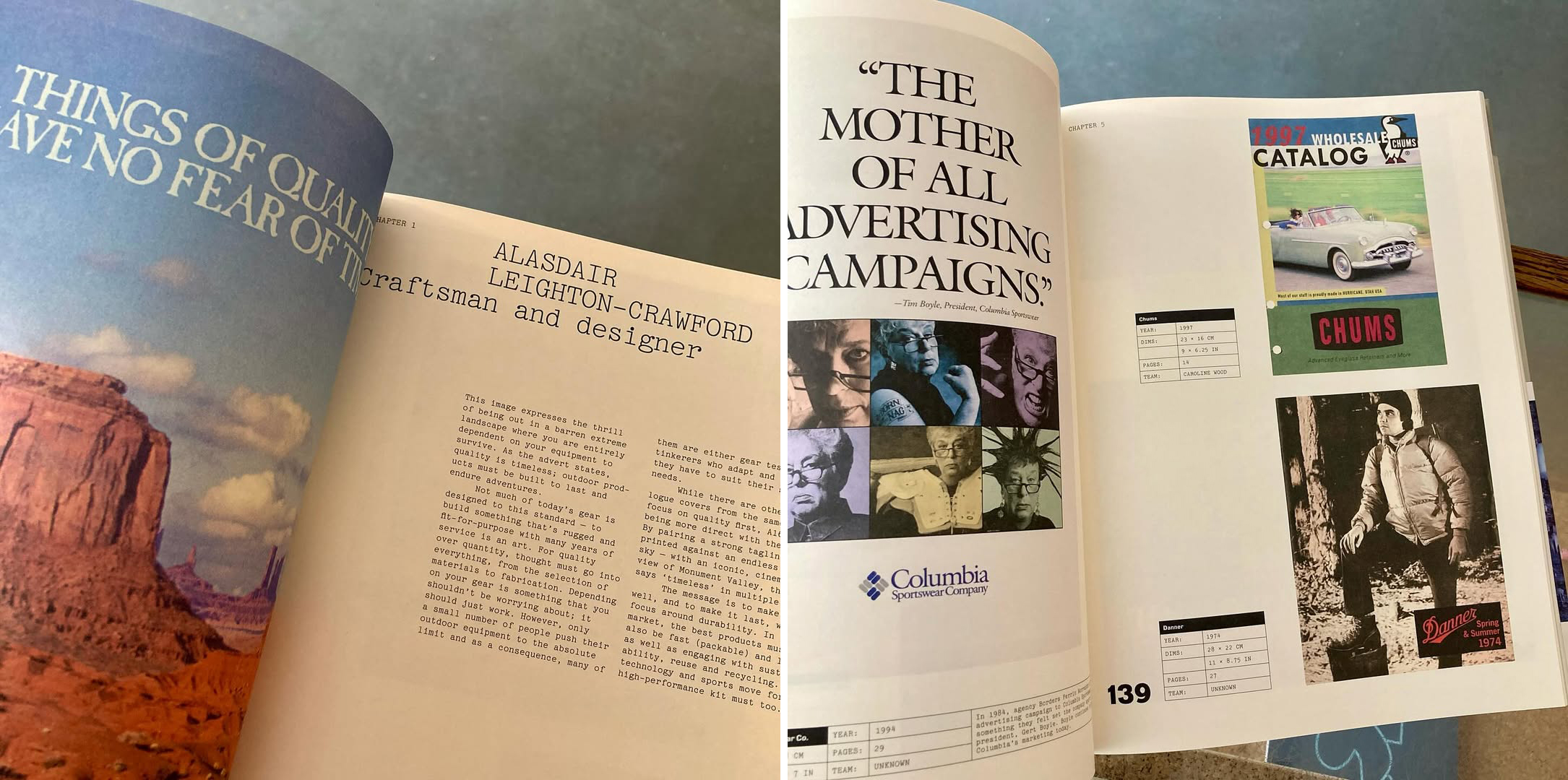

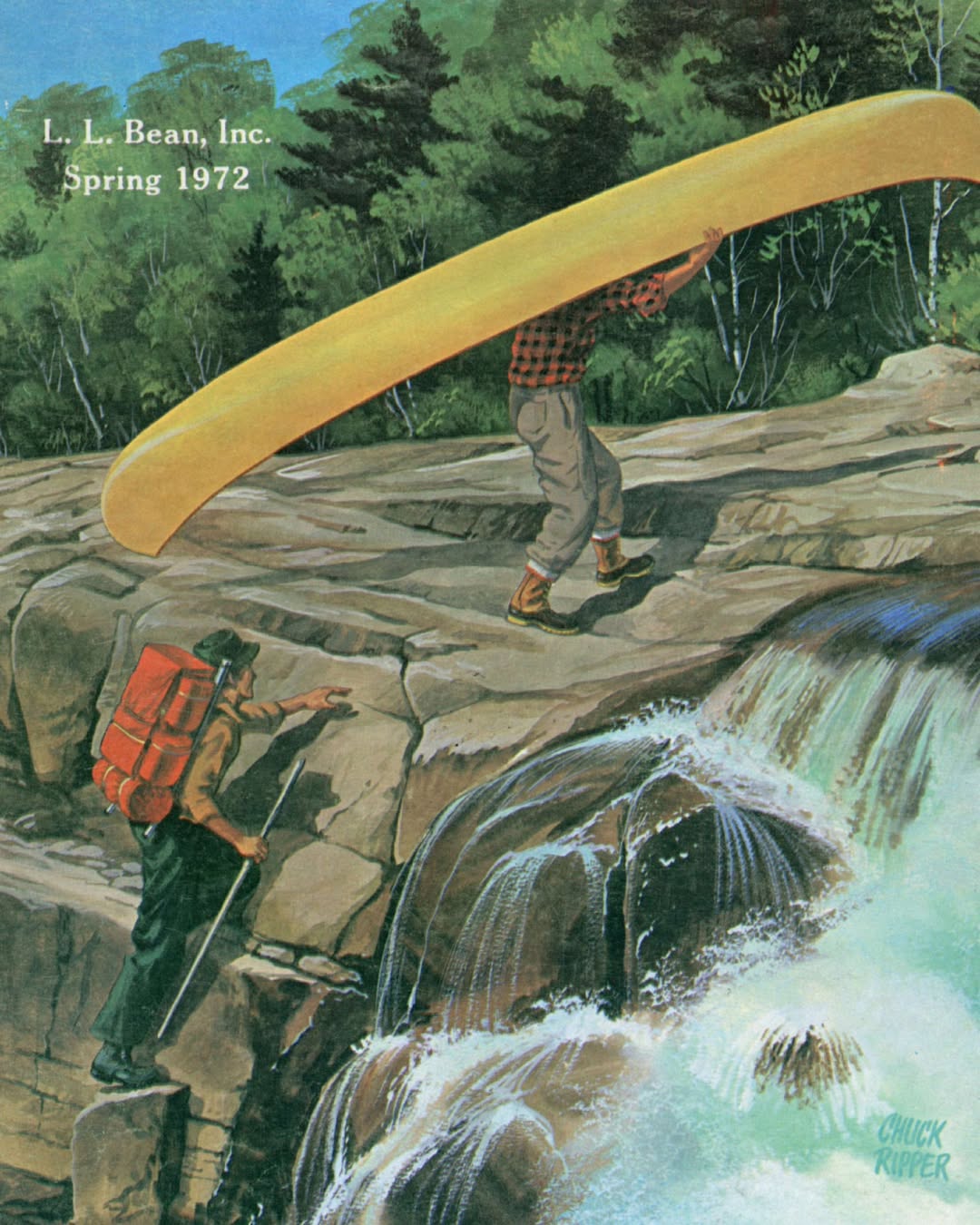

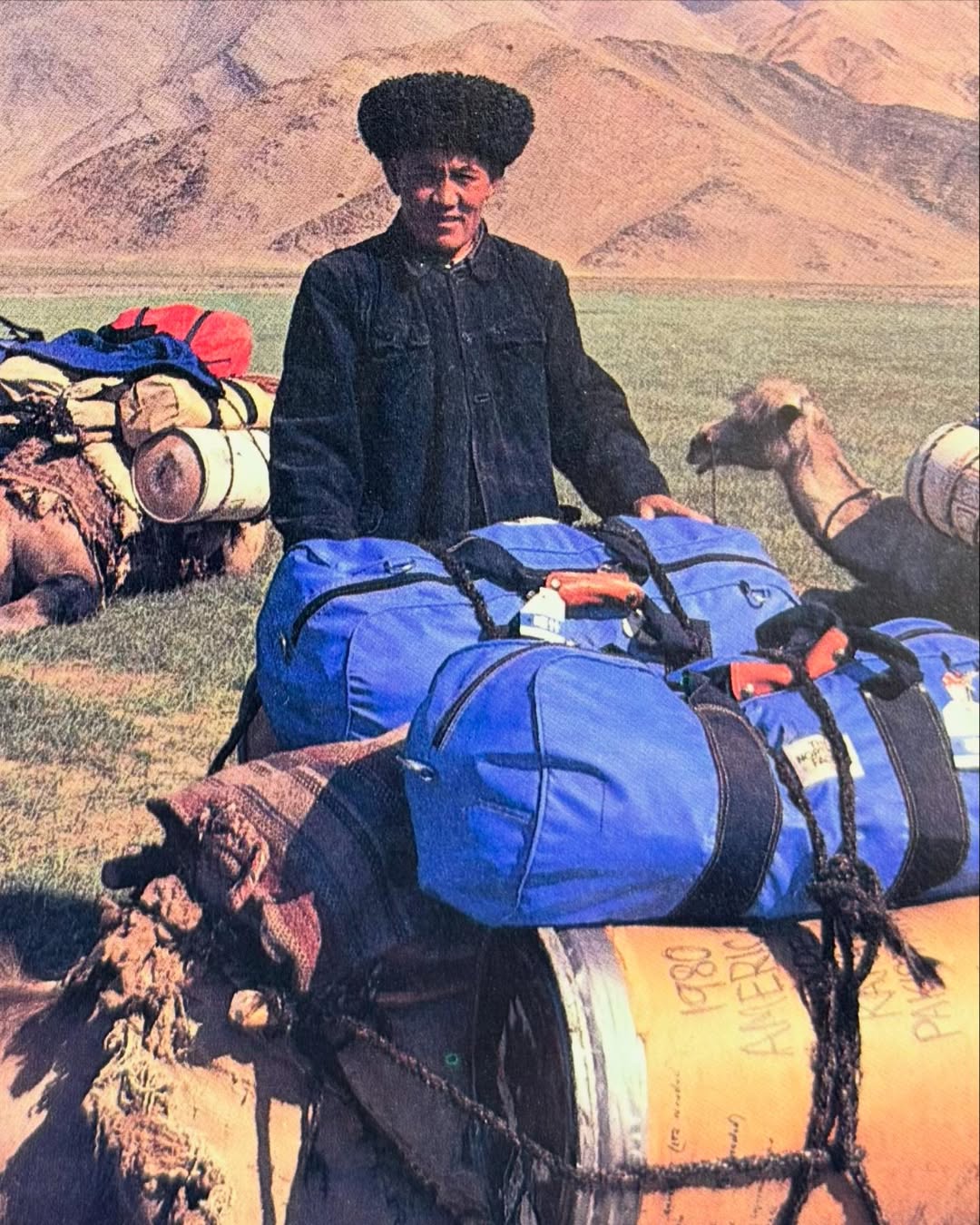

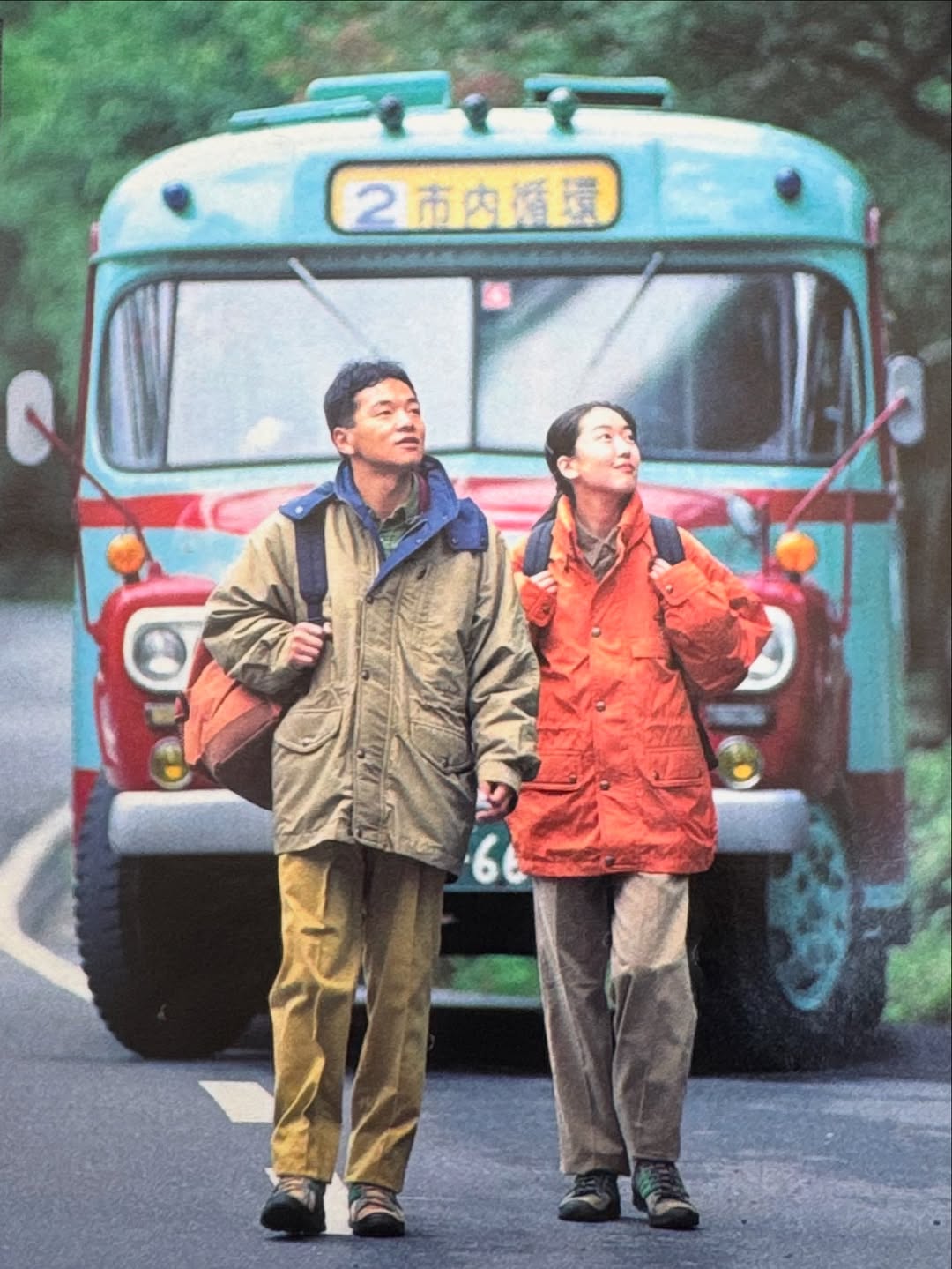

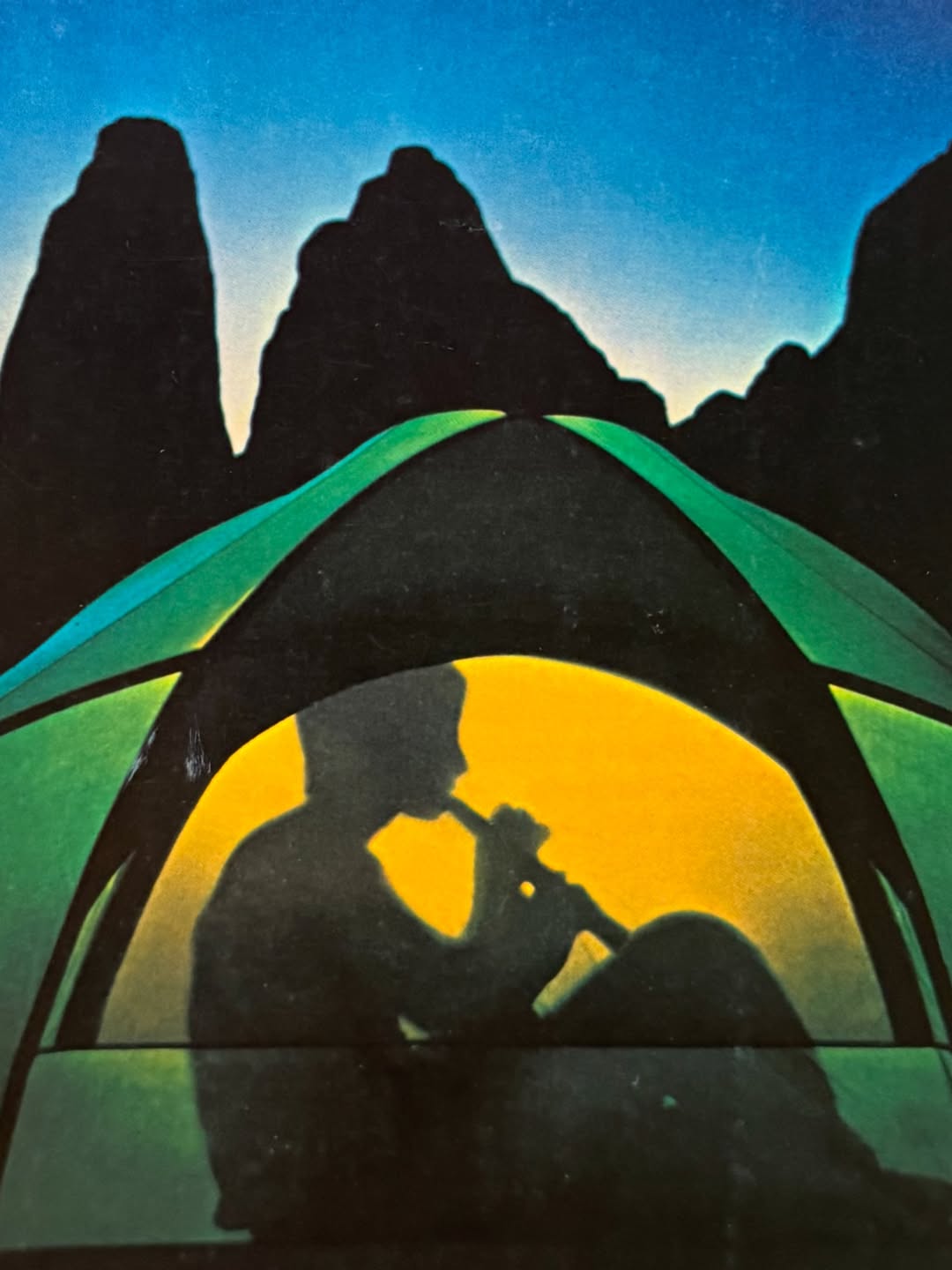

The Outdoor Archive is one of the rare exceptions. Like The Vintage Showroom or anything by Rin Tanaka — books I occasionally reference while writing — The Outdoor Archive is mostly about images, but only ones that you won’t easily find online. The book grew out of the Outdoor Recreation Archive at Utah State University, which houses some 7,500 catalogs from more than 1,000 brands, many dating to the early 1900s, alongside manuscripts, magazines, VHS tapes, photography collections, and designer sketchbooks. I first found their Instagram a few years ago and felt as though I’d uncovered a secret trove of outdoor ephemera. The book delivers that same thrill — but deeper — and adds thoughtful essays by David Marx, Avery Trufelman, and Rachel Gross.

Earlier this year, I chatted with authors Chase Anderson and Clint Pumphrey, who co-founded the archive in 2018 and have since grown the archive to what it is today. We talked about how they built such an extraordinary collection, the surprising gaps in outdoor brands’ own histories, and what their work reveals about the culture of gear.

You have such an incredible and expansive archive. How do you get these materials?

Chase: There’s a lot of internet sleuthing. We learned from Bruce Johnson, who ran the History of Gear website, which has this charming 1990s feel. He interviewed gear pioneers and published their stories, such as how Gerry and Ann Cunningham started Gerry Mountain Sports in Colorado after World War II. I would go through his site, look up the people on social media or try to find their phone number, and then just reach out. Over time, we built a pretty good network, and people started donating. We became known as the place where, if you have old catalogs or founded a company, we were a place where people could preserve this history. Most of our collection is donated, although Clint also has a small budget for acquisitions. We both spend a lot of time on eBay.

I’ve been surprised by how many storied, heritage companies don’t have archives. And how some companies, such as LL Bean, put a lot of effort into preserving their history. Are there certain company archives that you’ve seen and been impressed by?

Chase: Carhartt does an excellent job — their archivist Dave Moore has built out a strong garment and product collection. Eddie Bauer was long considered the standard, with their archivist Colin helping other brands learn how to establish archives. Patagonia’s archive is very strong, with a mix of printed materials, photographs, and gear. L.L. Bean’s archive is also impressive, and they’ve opened it to companies such as Todd Snyder to do collaborations. But many companies have little or nothing left and are trying to piece their histories back together.

Have any brands come to your archive to go through materials?

Chase: Yes, quite a few. It has been interesting to see how our archive visits diverge from what you’d normally expect. Typically, working in an archive is a solitary experience — just you, the materials, and one box or folder at a time, in silence. We’ve expanded that a bit. Designers and creative teams often want to spread out and work together, so we use our larger book room, where they can review materials collectively. That shift has been exciting. We’ve hosted The North Face a number of times, and their leadership really values reconnecting with their history and iconic products. We’ve also had Trek Bicycles, MSR out of Seattle, and even Allbirds, which was one of our very first visits — they brought a group of about 15 designers.

Allbirds is a fairly new company, so I assume they’re going through the archive to get design ideas?

Chase: Yeah, it was a research trip to explore for future products. We’ve also hosted Beams, which was particularly fun. They brought out a crew of four people, along with some people from Japanese magazines. Their chief buyer, Shigeru Kaneko, has a collection of vintage outerwear — which includes something like over 80 down jackets — and he wanted to look at the catalogs that corresponded to things in his collection. That turned into a book called Outdoor Expedition Book, which features photos of him doing research in our archive. It’s part of Beams’ I Am Beams series, where they let employees create books around their personal interests. For example, one was about tennis clothing and gear, while Shigeru’s focused on vintage outerwear.

When brands visit, what do they usually ask for?

Clint: It’s really a mix. Some companies don’t have much documentation from their early years, so they come in wanting to reconnect with their own history and heritage. Others arrive with specific projects in mind — maybe they’re designing a trail-running shoe and so they want to look at vintage footwear, or they’re working on a backpack and want to see catalogs from brands like JanSport, Gregory, or Osprey. Since the archive has more than 7,500 catalogs, it can be overwhelming to dive in cold, so we usually work with them ahead of time to curate a manageable set of materials. Then, when they arrive, we set them up in a classroom space where they can spread out, share ideas, and take photos of what they’re finding.

Do you have personal favorites from the collection?

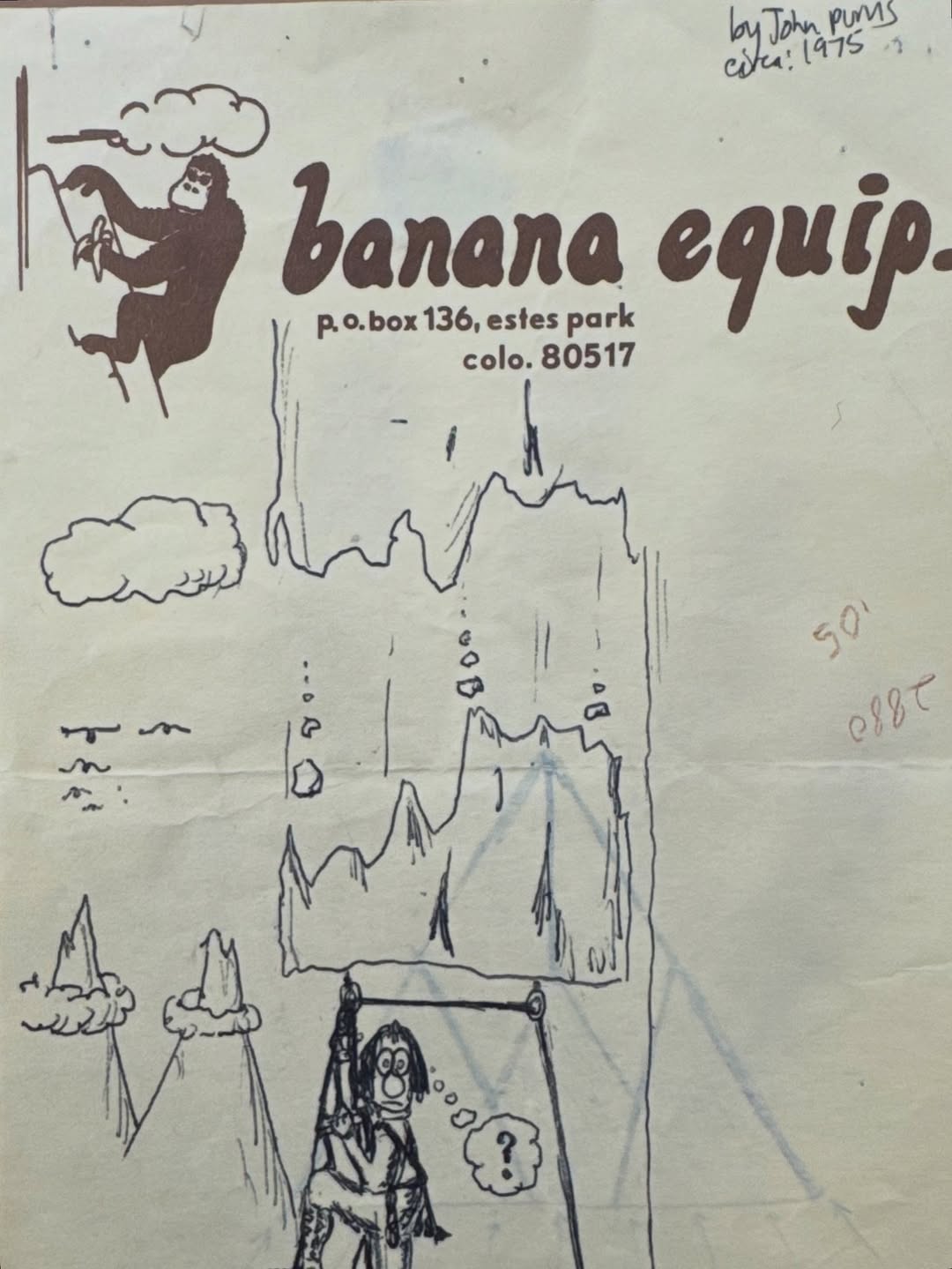

Chase: That’s a tough one, because we’re always bringing in new items that quickly become favorites. But there are a couple I keep coming back to, often quirky outdoor companies that were a flash in the pan, but they had fascinating stories or real influence. One is a defunct brand called Banana Equipment. Their tagline was “Product with Appeal;” their logo showed a gorilla holding a sewing machine in one hand and a banana in the other. They started in the late ’70s and were one of the first companies to use Gore-Tex — influential in that sense — but also emblematic of a less corporatized outdoor industry. We’re lucky to have their catalog collection, donated by the founder, which includes truly one-of-a-kind materials like their first hand-drawn catalogs.

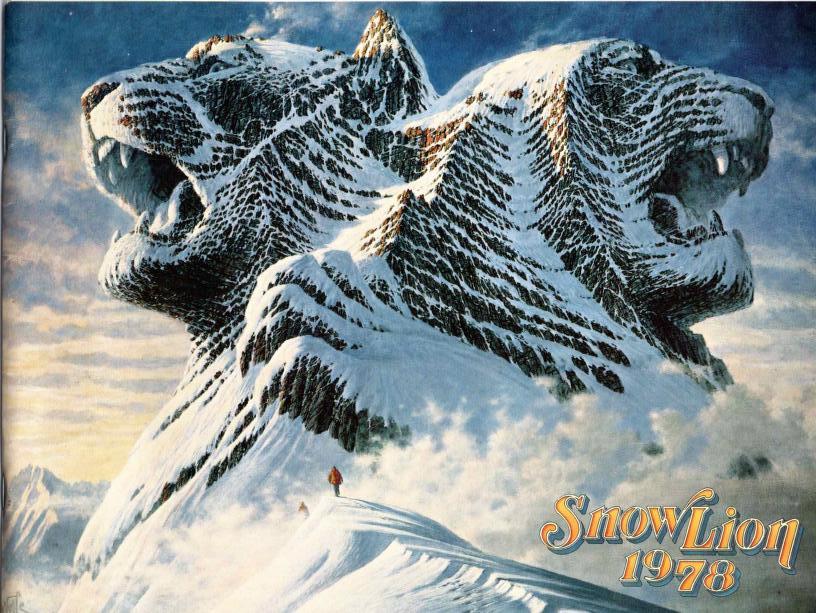

Another favorite is Snow Lion, also defunct. One of their catalog covers is unforgettable — it’s essentially a painting of two mountain peaks shaped like lion heads, pointed in opposite directions, with a tiny climber making their way up. It’s majestic, completely over the top, and incredible. Those two stand out among many. We also have manuscript collections that are just as remarkable, but in terms of catalogs, Banana Equipment and Snow Lion are special.

Clint: I love a 1970 North Face catalog that came in a box the size of a deck of playing cards. It unfolded into a poster with stylized photos and coupons for restaurants and ski tickets. Another favorite is our collection of outdoor clothing kits from the 1970s and 1980s. So you would order a parka, but companies would send you fabric, down, zippers, and instructions so you could sew your own parka at home. It’s an interesting peek into a time of outdoor clothing when it was still possible to make something similar to what you could buy in a store. You didn’t need all this special equipment, like seam welders.

I used to buy old LL Bean catalogs off eBay and noticed that the really old ones — such as the ones founder Leon Leonwood Bean would be involved in — contained essays on how to do things outdoors. Such as how to build a fire or pitch a tent. Do you see such editorials in other catalogs?

Chase: Yes. Jerry Mountain Sports, founded by a 10th Mountain Division veteran after World War Two, focused heavily on education. They published pamphlets like “How to Keep Warm,” “How to Camp,” or “How to Go Backpacking and Enjoy It.” They were a really interesting company because they were making high-performance products for expeditions, but they also invented the kitty carrier so the whole family could go out. They were doing a lot of education for people who were just getting into the outdoors. There was also Chouinard (later Patagonia) and MSR. Their catalogs were almost like newsletters, which contained information about climbing and climbing equipment. They were very text heavy, as they had data on how they tested equipment and even manifestos like the “clean climbing” philosophy, which was about climbing without damaging the rock faces.

Clint: A lot of that came down to the fact that these were new products, and companies had to educate consumers on why they were better than what came before. Gore-Tex is a good example. Most people had no idea what it was or how it worked, so brands had to demonstrate it in simple ways. We have one of the classic “coffee cup tests” in the archive, which Marmot used in the early years. It’s just a square of Gore-Tex, a rubber band, and an instruction sheet. The instructions told you to boil water, stretch the Gore-Tex over the top of a mug, and secure it with the rubber band. You’d see steam rising through the fabric, but when you turned the cup upside down, the water wouldn’t leak out. It was a clever way of showing both breathability and waterproofing — essentially using supplemental material to teach consumers what they were buying and why it was an improvement.

Your archive spans 100 years. Would you say there are some consistencies or trends in how things are presented?

Clint: I think a lot of the imagery has stayed remarkably consistent. Outdoor catalogs have long been aspirational — showing stunning mountain peaks and suggesting, implicitly, “you can summit this with our gear.” That combination of beautiful landscapes and people using equipment in the outdoors goes back at least as far as early Abercrombie & Fitch catalogs. So even as other things have changed, that visual language has remained steady.

Chase: From the product side, there have been big changes, but also some surprising consistencies. Every brand has always been chasing the same goals — gear that protects you and actually performs. In the early 1900s, companies leaned on natural materials like Ventile cotton, and their catalogs talked about the performance qualities of those fabrics. Today, it’s synthetics making the same case. So even though the materials and innovations look different across decades, the focus on functionality has been a common thread running through it all.

Rachel Gross, who contributed an essay to your book, has written about how outdoor brands often use marketing to shape identity and signal belonging, even for people who may not spend much time in the wilderness. How do you see catalogs contributing to these narratives of identity and necessity?

Clint: From what I’ve seen through this project and at trade shows, a lot of companies have pushed the idea that you need cutting-edge technology for even the most mundane activities. Gore-Tex is a good example, marketed as essential even for walking from your car to the grocery store. Lately, though, there’s been some pushback against that narrative. People are recognizing that natural fibers can be better suited for shorter periods outdoors and may also be more sustainable. So the story brands tell about what kind of gear you “need” is starting to shift.

Chase: I don’t know if this directly answers your question, but your point about city people buying the “right” gear in order to feel qualified to go outdoors really resonates. That narrative has been around for a long time. Early Abercrombie & Fitch catalogs, for example, seemed to suggest you needed their products in order to be properly equipped. But what’s interesting is that Abercrombie, based in New York City, also embraced the opposite idea. One of their taglines was “From the Blaze Trail to the Boulevard,” which implied that their clothing wasn’t only for expeditions — it could be worn in city life as well. Today, when brands promote the idea of “from the mountain to the bar,” it can seem new, but companies like Abercrombie were already playing with that identity decades ago. To me, it shows that questions of who gets to wear outdoor clothing — whether it’s reserved for “real” outdoor enthusiasts or open to everyone — have always been part of the conversation.

Clint: And the archive really backs that up. Outdoor clothing has long been used to communicate values as much as function. It’s not just about a logo on a jacket. In the 1970s, for instance, REI sold bold graphic T-shirts with environmental imagery. That’s a clear example of companies leaning into the idea that clothing can express personal beliefs and identities, not just provide technical performance.

I also read Avery Trufleman’s essay in your book, and I thought she made a really interesting point. It connects to the Abercrombie tagline Chase just mentioned — “From the Blaze Trail to the Boulevard.” Trufleman argues that even splitting the outdoors and the city into two separate categories can be a false dichotomy. After all, you still need forms of protection in urban environments, so it’s not always a clear-cut division.

Clint: I think that’s a fair point. It’s not accurate to say the outdoors only means trails and mountains. For some people, it’s a city park or even a walk to work. The definition is broader than the industry sometimes acknowledges.

Chase: I was just talking about this yesterday with an early North Face employee. The outdoor industry can have a very narrow idea of what “counts” as the outdoors, but people constantly push those boundaries. A good example is in the 1990s, when hip hop communities embraced brands like The North Face and Columbia. They were using the gear in ways the industry hadn’t originally imagined, but that were still very much about needing protection outdoors.

Clint: And this isn’t a new tension. Back in the 1920s, Abercrombie’s founders actually split over this issue — David Abercrombie left the company because he thought Ezra Fitch was catering too much to city people and not to “real” outdoorsmen. So the debate over who gets to wear outdoor gear, who counts as an insider, and who’s just posing has been around for a long time.

One thing I noticed while going through your book — and it mirrors my own experience with outdoor gear — is how strongly certain eras resonate. When I think of the backpacks I’d want to own, it’s 1960s and ’70s Gerry. When I think of parkas I want to wear, it’s the classic 1970s and ’80s Sierra Designs. I was constantly wowed by the imagery in the catalogs, but I admit that feeling fades once I reach the 1990s and early 2000s. Maybe that’s just because I lived through that period, so the designs feel familiar. I remember seeing them in specialty stores at the time, and they don’t have the same mystique. Do you think there really was a “golden age” of outdoor design, in terms of both products and presentation, or is it more that we always view the past through a lens of nostalgia?

Chase: I think it’s probably a little of both. My wife has younger Gen Z siblings, and for them the early 2000s are fascinating — that whole Y2K fashion look has come back. For me, though, those years were middle and high school, and I’d rather not revisit what people were wearing then. So nostalgia definitely plays a role. But when people talk about a true “golden era,” they often point to the 1970s backpacking boom. That was when more and more people were getting outside, and companies like Patagonia emerged in the ’80s while The North Face grew out of the 1960s and the environmental movement. That period is what many consider the classic golden age.

Clint: A lot of the companies that are household names today started very humbly — just a few friends who loved climbing or skiing, tinkering in their garages, making gear because it was fun. That informality really shows in the catalogs from those early years. They’re not sleek or polished, but they have a lot of character. And I think that’s something big corporations struggle with now — how to recapture that sense of authenticity and playfulness when you’re no longer just a couple of people building gear in a garage.

I’m curious, from your perspective: do you find the backpacks from the 1960s and ’70s more visually appealing than the modern backpacks you could buy today?

Chase: Aesthetically, yes. Functionally, modern gear is much better — lighter, more ergonomic, with features like hip belts and better ventilation. I much rather carry a frameless pack than an aluminum frame backpack

Clint: I’m looking around our office right now. Chase has some of his personal collection here, and it’s all from that era, mostly the 1970s. They definitely look cool, but I’m not sure how well they’d hold up on a week-long backpacking trip. I think that’s why, when you see a company re-release a design, they do it with updated materials.

Chase: The North Face is a great example. They recently celebrated the 48th anniversary of the Mountain Parka, one of their iconic pieces, by re-releasing it with updated materials for better performance and durability. We were involved in an event in Paris during Fashion Week that showcased this — a gallery space with archival imagery, an original Mountain Parka on display, and the new version being promoted. I think that shows how brands approach it: they love the old aesthetic, but they update it with modern materials and performance improvements.

I remember buying the re-release of Kelty’s Mockingbird backpack. Why don’t more companies re-release archival designs?

Chase: It’s a good question. I do feel like more companies are starting to do this now. The North Face has been re-releasing collections for the last few years — for example, they recently brought back their ’90s Steep Tech line. Prana has also leaned into this with their Prana Originals program, where every season or two they reissue vintage pieces but reimagine them for today. REI just re-released their Dome Tent, updating the materials but also building a small apparel line that pays homage to the tent’s design and colorway. Mountain Hardwear did something similar for their 35th anniversary, really leaning back into their early branding — the nut logo and the original colors — and tying that to some re-released products. So yes, I think we’re seeing more of these kinds of projects across the outdoor industry.

One thing I noticed while flipping through the book — and I think Clint alluded to this — is the strong DIY spirit in the early days, with people building gear in their garages. Chase also mentioned the 1960s and ’70s backpacking boom, when hiking packs and other products reflected that same energy of people heading outdoors in new ways. Do you see parallels today? Are there parts of modern outdoor culture that carry that same spirit — whether through DIY projects, small companies, or niche communities of enthusiasts creating social meaning around their gear?

Chase: That’s a good question. I’m not sure I can point to a specific brand, but what comes to mind is the way some creators are encouraging people to make or remake their own gear. Nicole McLaughlin and Jaimus Tailor — both contributors to the book — are great examples. They’ve helped people think about upcycling, customizing, or even building things themselves. I find it interesting how they empower consumers to learn a skill and create something unique. Even if it still carries, say, an Arc’teryx logo, it’s been reworked into a one-of-a-kind piece that reflects the maker’s own hand. To me, that’s very much in the spirit of DIY — not a brand-driven example, but a cultural one.

Is there anything in today’s outdoor culture that feels similar to the boom of the 1960s and ’70s — moments where people are engaging with the outdoors in a way that reflects that same spirit?

Chase: The closest comparison to the backpacking boom might be the modern ultralight movement. Companies like Ultralight Adventure Equipment here in Logan — which started in 2001, so really the early days of ultralight — and Hyperlite Mountain Gear both embody that spirit. It’s a passionate community that knows their gear inside and out. People go incredibly deep, weighing every single gram in their packs and obsessing over performance. I was just at ULA today, and their fans are genuinely fanatical about the products. That kind of intensity and community reminds me of the energy around backpacking in the 1960s and ’70s.

Clint: We’ve also worked with people who are relaunching defunct brands or buying the rights to old companies, often for the Japanese market, where there’s strong interest in heritage outdoor gear. For example, someone recently relaunched Holubar, which was one of those golden-era companies. We’ve also worked with the group that owns the rights to Jerry in Japan. Even locally, one of our professors, Bob, bought the rights to Rivendell Mountain Works — best known for the Jensen Pack — and plans to do small, handmade releases from time to time. That’s where you see the really homegrown feel return: not large-scale operations trying to sell millions of backpacks, but small-batch, garage-style production that reimagines these historic designs with real craftsmanship.

What’s next for the archive?

Chase: More collecting, but also more accessibility. We’ve done a lot of collecting already, and we’ll keep at it — we have a long list of people we’re talking to about donating materials. But just as important is bringing the archive to people. That means hosting more design teams on campus and taking the archive out to events. Every spring and fall, we go to Portland for the Functional Fabric Fair, where we curate a new exhibit each time and visit brands to share the collection. We’ve also started a Substack newsletter to share stories and updates, and we run the Highlander Podcast, which includes oral histories with gear pioneers. For instance, I recently interviewed the designer of Patagonia’s logo from 1975 — someone whose name you won’t even find online.

Clint: The nice thing about creating an archive around a topic no one has really collected before is that there’s no shortage of work to do. We’ll keep building the collection and, ideally, free up more of our time to focus on it. It’s important work — the archive not only preserves the history of outdoor gear, but also helps train the next generation of designers in the industry. At this point, I think we’ve positioned ourselves as the hub for that history.

Many thanks to Chase and Clint for chatting with me. Readers can pick up a copy of The Outdoor Archive through Bookshop.org, which is an alternative to Amazon that allows you to support independent booksellers. You can also follow them on Instagram, where the images above are from. Lastly, you can find more outdoor catalogs at the The Daniel D. Teoli Jr. Small Gauge Film Archive online (some of the photos above are also from there).