It is a grim feature of modern life that we treat downtime as a pit stop between bursts of usefulness. In the United States, where the Protestant work ethic took the deepest root, even Sabbath observance was shaped by the belief that unproductive time required moral justification. Writing in the early 1930s, Bertrand Russell warned that “immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous.” By 1948, the German philosopher Josef Pieper offered a more forceful philosophical defense of leisure. His book Leisure: The Basis of Culture, published in the wake of one of the largest labor strike waves in US history, pushed back against what he called the tyranny of “total work,” a condition in which the modern human is reduced to their measurable productivity.

If leisure needs any justification at all, it can be found in the breakthroughs it enables: Darwin doing his deepest thinking during long walks at Down House, Beethoven composing “Symphony No. 6” in the countryside, Newton developing the foundations of calculus while on a two-year leave from Cambridge. But framing leisure in terms of output, or even as a way to rejuvenate us for labor, still reduces it to an instrument of the state or market. Instead, Pieper argues that leisure is a necessary condition for the soul. The Greek word for leisure, scholē, is the root of our word school—not a site of vocational training, but a space for contemplative stillness. Leisure ensures that “the human being does not disappear into the parceled-out world of his limited work-a-day function, but instead remains capable of taking in the world as a whole, and thereby to realize himself as a being who is oriented toward the whole of existence.”

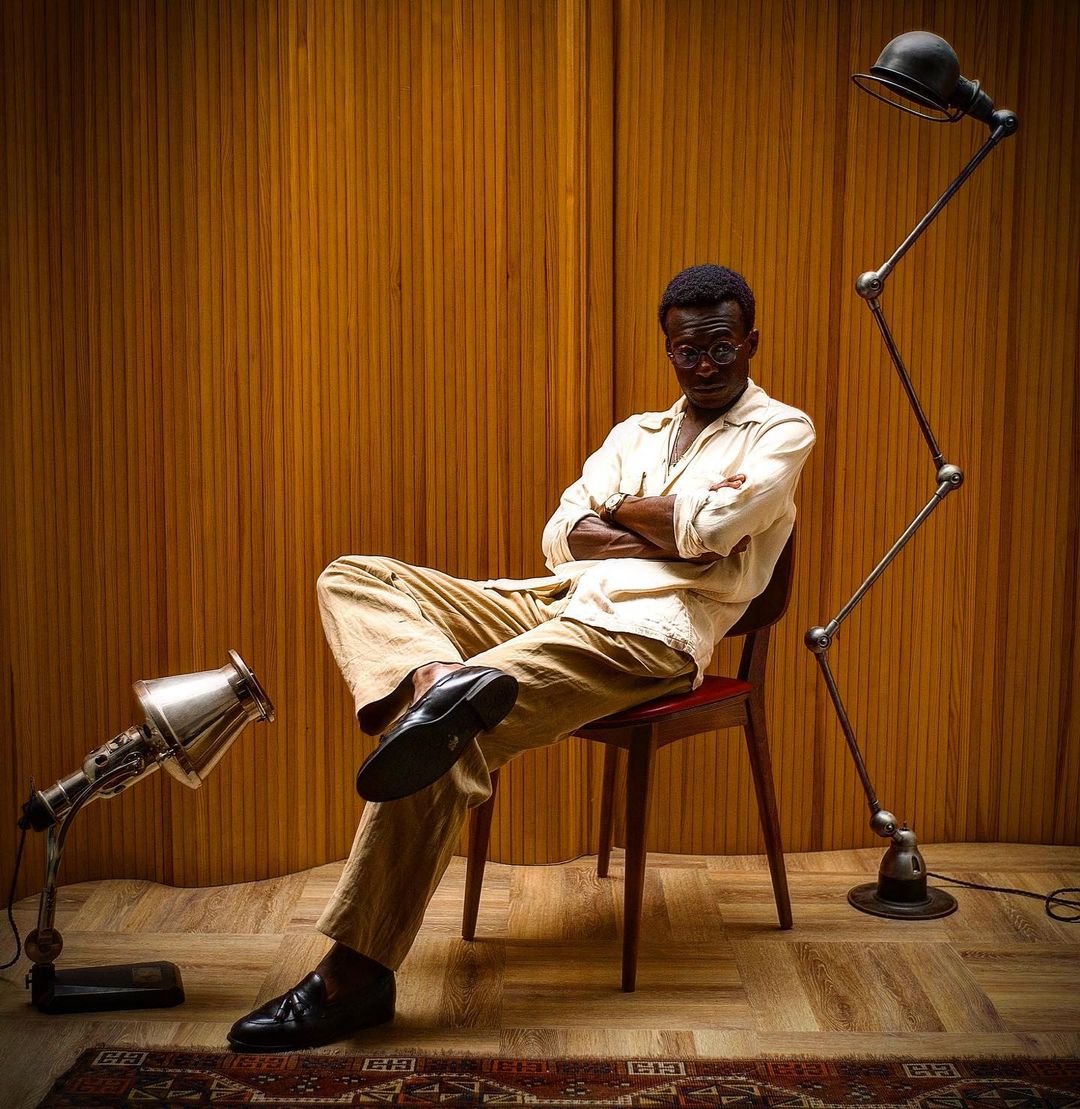

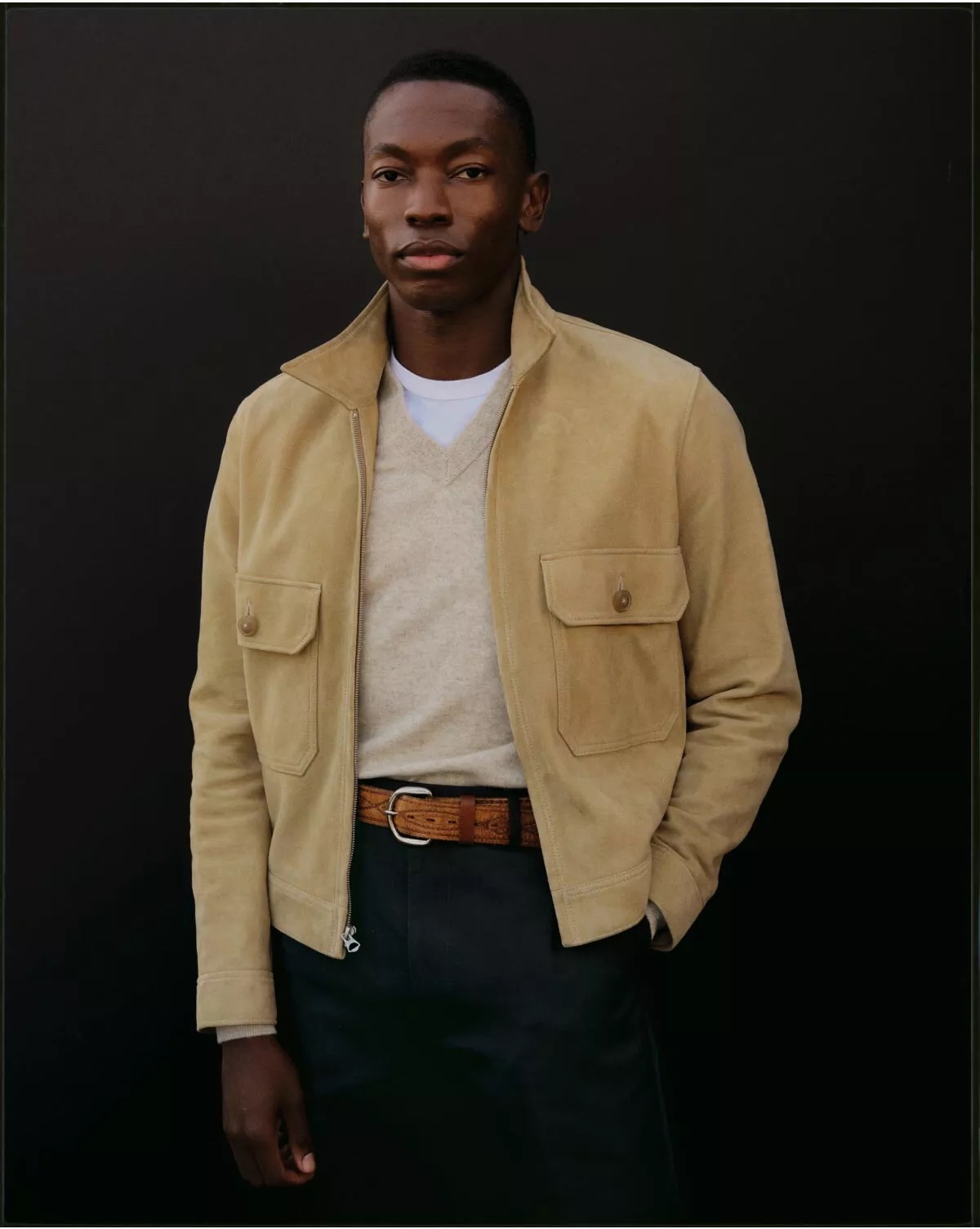

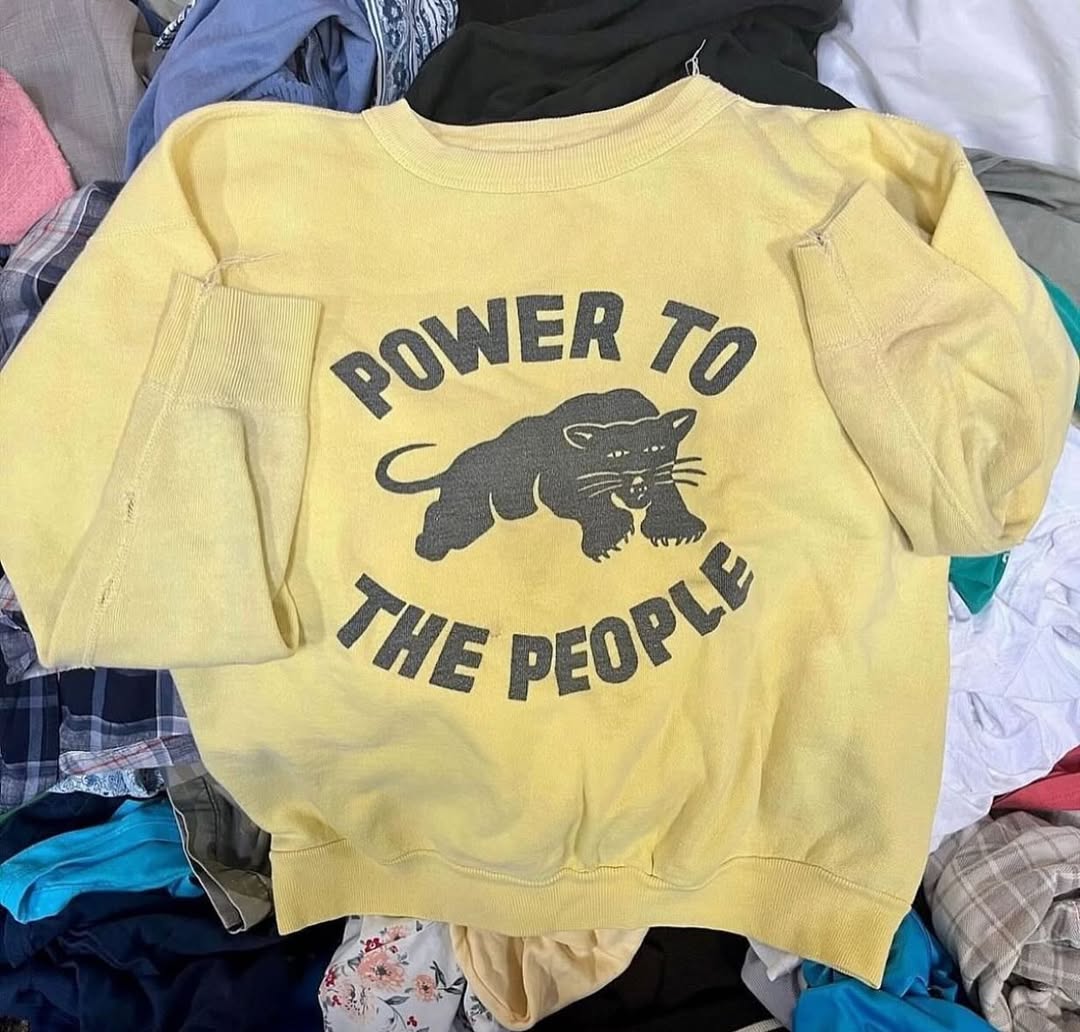

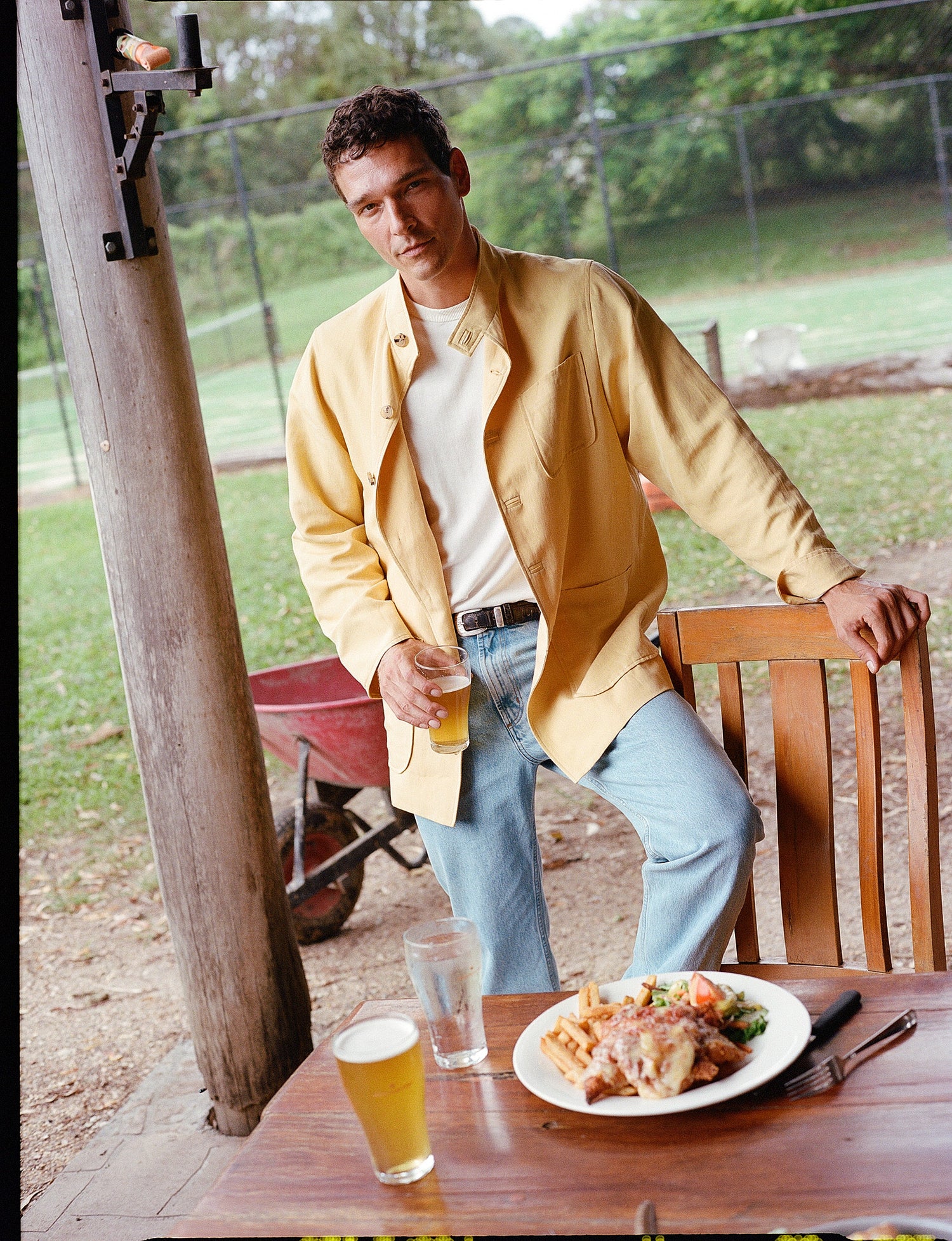

In the last few years, I’ve been doing a series called “Excited to Wear.” It’s my way of sidestepping the pointless exercise of defining menswear “essentials,” a concept that flattens the richness of style into generic shopping lists. Instead, I prefer to discuss clothes that excite me as the seasons shift. This spring, I’m drawn to clothes that reflect work and leisure—not as polar opposites but as parallel expressions of human wholeness. After all, spring and summer are the seasons for idleness, marked by bikes that creak out of garages and folding chairs that live in trunks. This list is about the clothes I like to wear for light work on warm afternoons and dawdling on cool evenings. It’s clothes for gardening, brunch, and listening to rediscovered LPs. Hopefully, you can find something here that inspires you for your wardrobe.

The Lounge Loafer

If menswear lore is to be believed, King George V—father to the idiot savant and original menswear influencer, the Duke of Windsor—once commissioned a pair of unlined, nondescript slip-ons with skin-stitched tips for ambling indoors. Those shoes, first made by Wildsmith, eventually evolved into Edward Green’s Harrow, an iconic penny loafer. A similar spirit has returned in recent years, as brands like Stoffa, Bode, and Lemaire adapt traditionally domestic footwear for life outside the home. I’ve admired the look on others, but those styles never felt right for me.

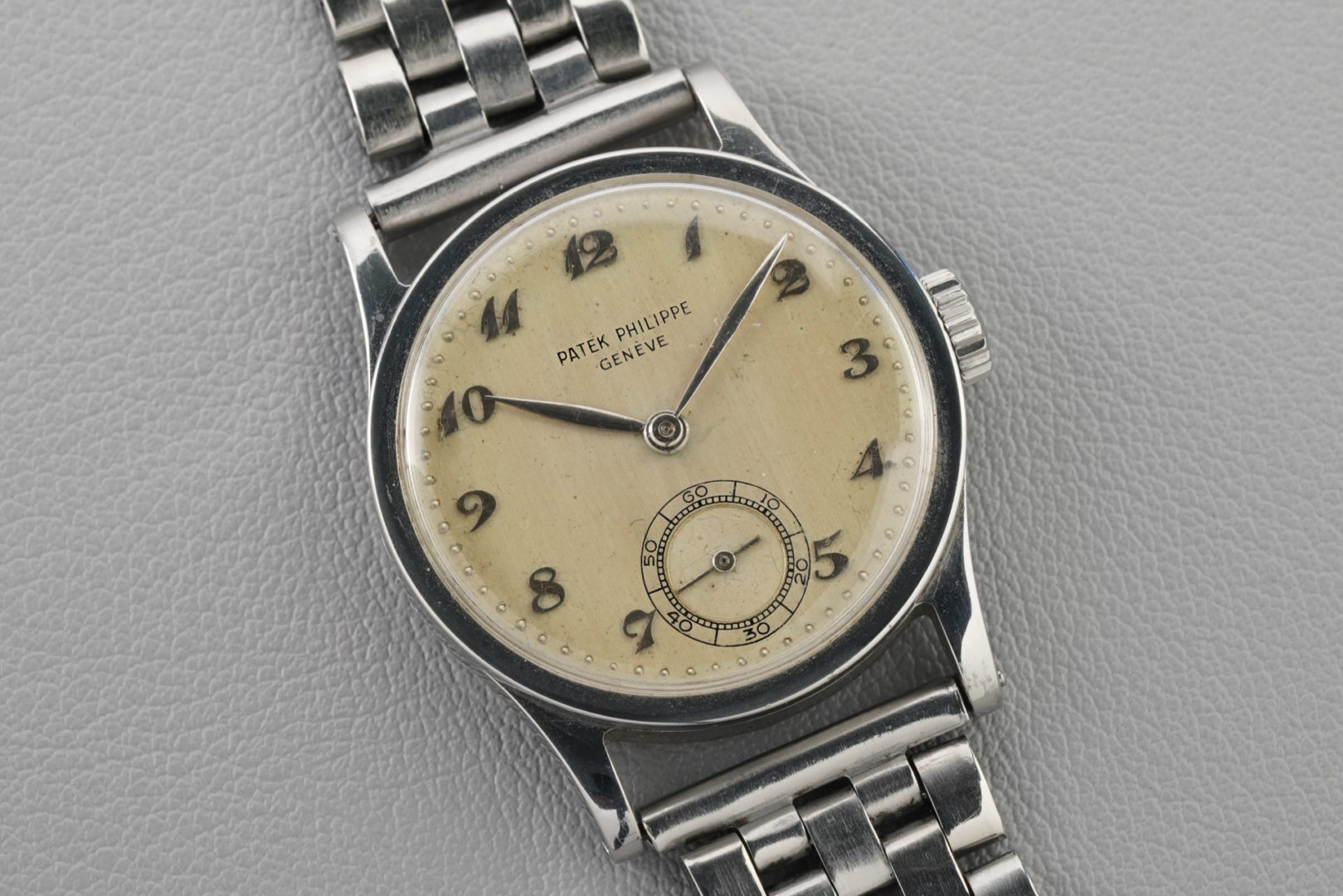

However, I recently picked up a pair of loafers from August Special, a relatively new label founded by Joseph Pollard in 2022. Pollard has an impressive résumé, with design roles at Duffer of St George and Best Made Company. During his ten years at Ralph Lauren, he designed outerwear for Polo, contributed to Purple Label collections, and sourced vintage pieces for the brand’s boutiques. He also led design teams at Double RL, which might explain why his loafer, charmingly named Augie, feels so compelling.

The Augie shares some DNA with the Prince Albert, a slip-on style named after Queen Victoria’s consort, whose death famously triggered her lifelong mourning and cemented Victorian England’s association with the color black. Traditionally made in velvet, the Prince Albert was historically worn with evening clothes at home; however, over time, it migrated into other black tie settings, becoming yet another example of a domestic style reinterpreted for public life. The Augie, by contrast, feels less formal, perhaps due to the thicker sole and absence of grosgrain binding along the shoe’s topline. Given Pollard’s design background, it feels like precisely the sort of lounge shoe you’d wear with Double RL. It’s more refined than Sabah’s bohemian slip-ons, yet more rugged than Bode’s Grecian-inspired slippers, making it equally at home with J. Crew’s linen shorts, Levi’s bootcut jeans, or Imogene + Willie’s camo fatigues.

The sizing and break-in process were not easy. The Augie loafer is built on a subtly curved, banana-shaped last, similar to Alden’s Modified, and the brand recommends taking your Alden size. But since Alden’s sizing varies from last to last—the Aberdeen fits differently from the Barrie—I wasn’t quite sure what to order. I ended up going a half size down from my Brannock, which is what I typically wear in the Barrie. However, the Augie has an unusually narrow heel, which badly scraped my ankle on the first day. My advice: ease into them with a thin pair of dress socks and short walks around your house or neighborhood. After a week or two, they soften up and conform to your feet.

Having worn mine regularly now, I’ve grown quite fond of them. I wouldn’t recommend them as a first pair of loafers—more traditional styles, such as penny loafers, tassels, or even camp mocs, are better starting points—but for those looking to expand their rotation, they’re a compelling option. The “Classic” version features a thin rubber sole, best suited for light use, while the Goodyear-welted model offers greater durability with its single-leather sole. I think they look particularly handsome in suede.

If you’re looking for something that pairs more easily with tailoring, consider The Anthology’s Torbay or P. Johnson’s Alfresco. Those are even more refined than the Augie. Belgian Shoes are, of course, a classic choice. If you’re testing the waters and want something more affordable, Yanko offers a solid entry point. All of these can be a great way to introduce a more relaxed, loungey vibe to both tailoring and workwear.

Options: August Special, La Botte Gardiane, Stoffa, Bode, Lemaire, Bryceland’s, The Anthology, P. Johnson, Arthur Sleep, Belgian Shoes, Yanko, Baudoin & Lange, Drake’s, Loro Piana Open Walk, and SuitSupply

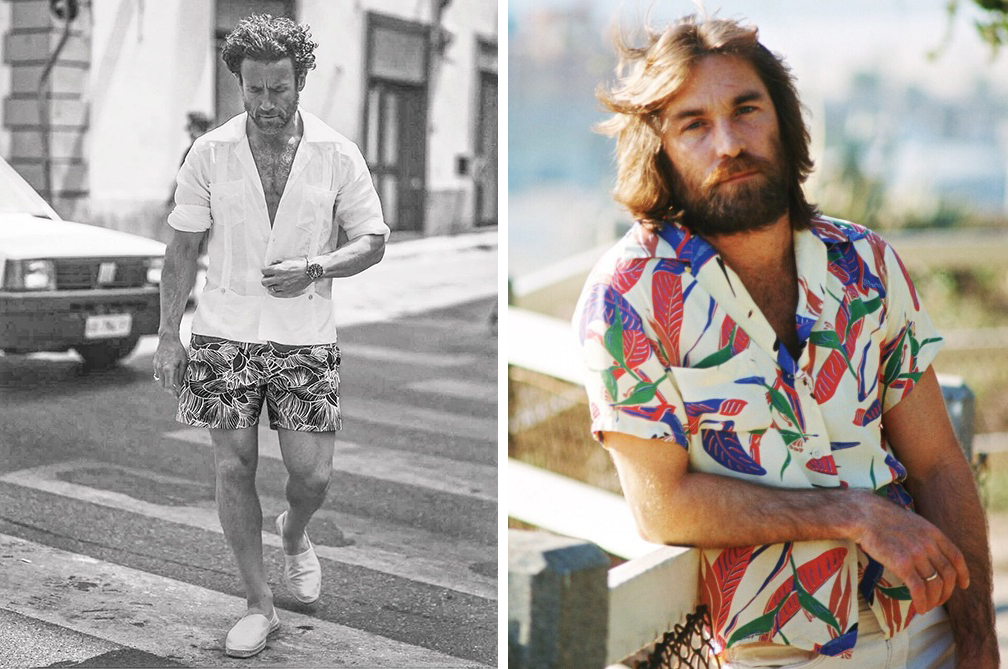

The Easy Camp Collar Shirt with Shorts

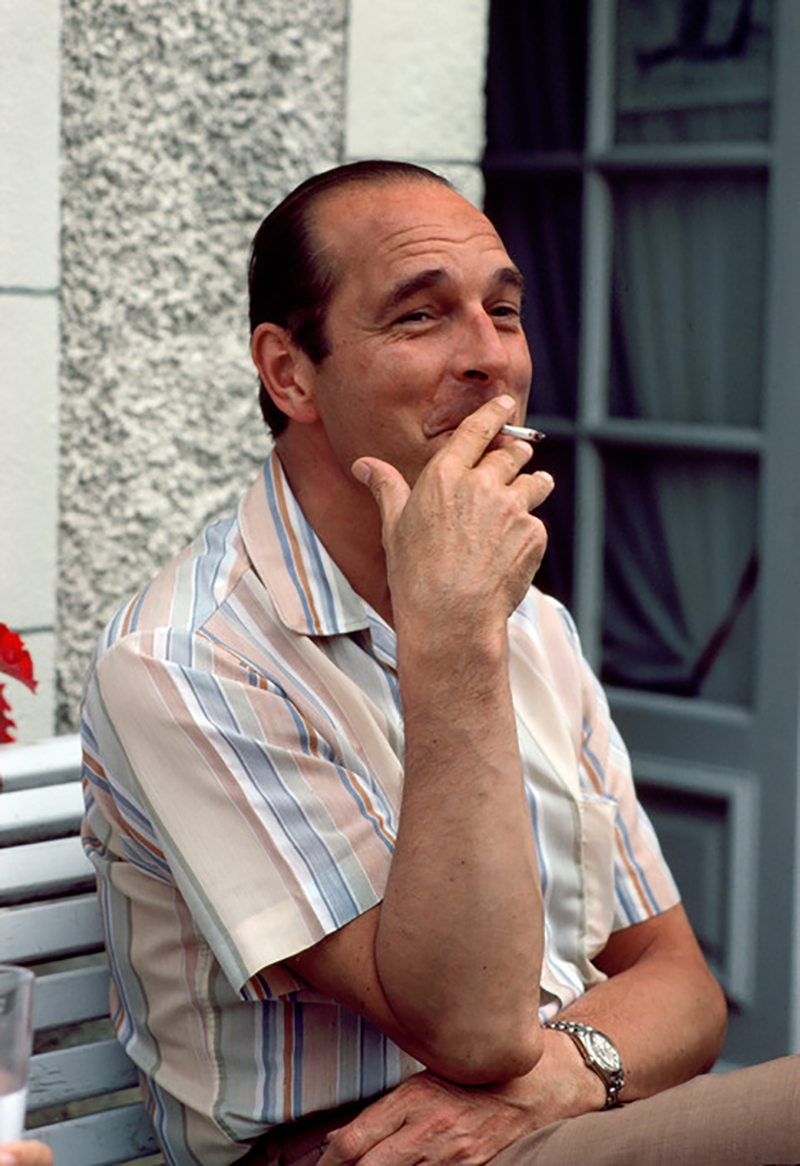

For me, the classic summer outfit will always start with a camp collar shirt. Paired with tropical wool trousers and penny loafers, it can feel quietly refined; worn with shorts and espadrilles, it looks casual but composed. It’s the look of Greek men playing cards by the sea, or Havana locals drifting through the city in linen and leather sandals. In black-and-white photos of stylish men in warm climates, you’ll often spot dual-pocketed camp collar shirts, some with a ribbed tank tucked underneath. The collar frames the face better than a T-shirt but carries none of the stiff ceremony of business button-ups.

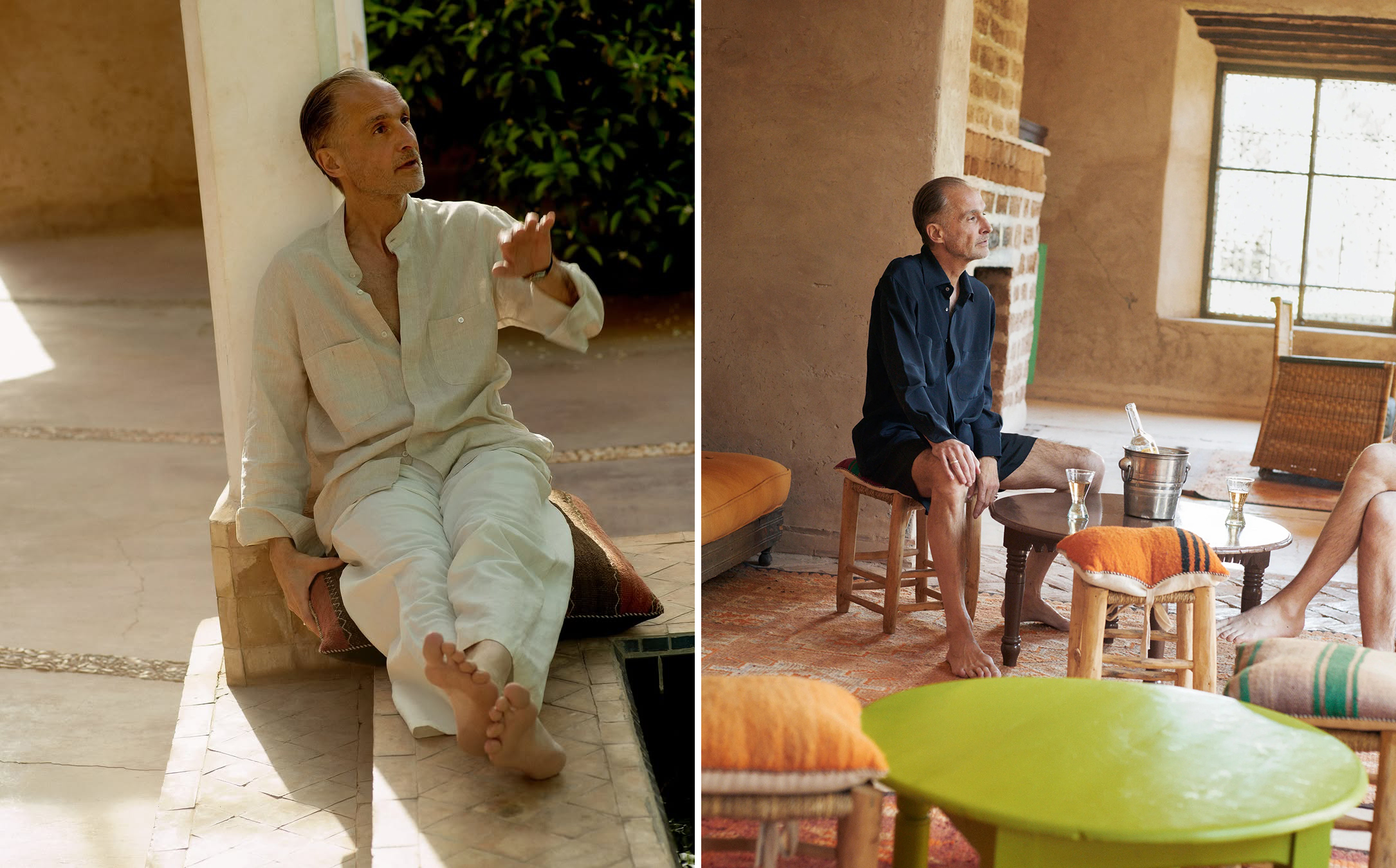

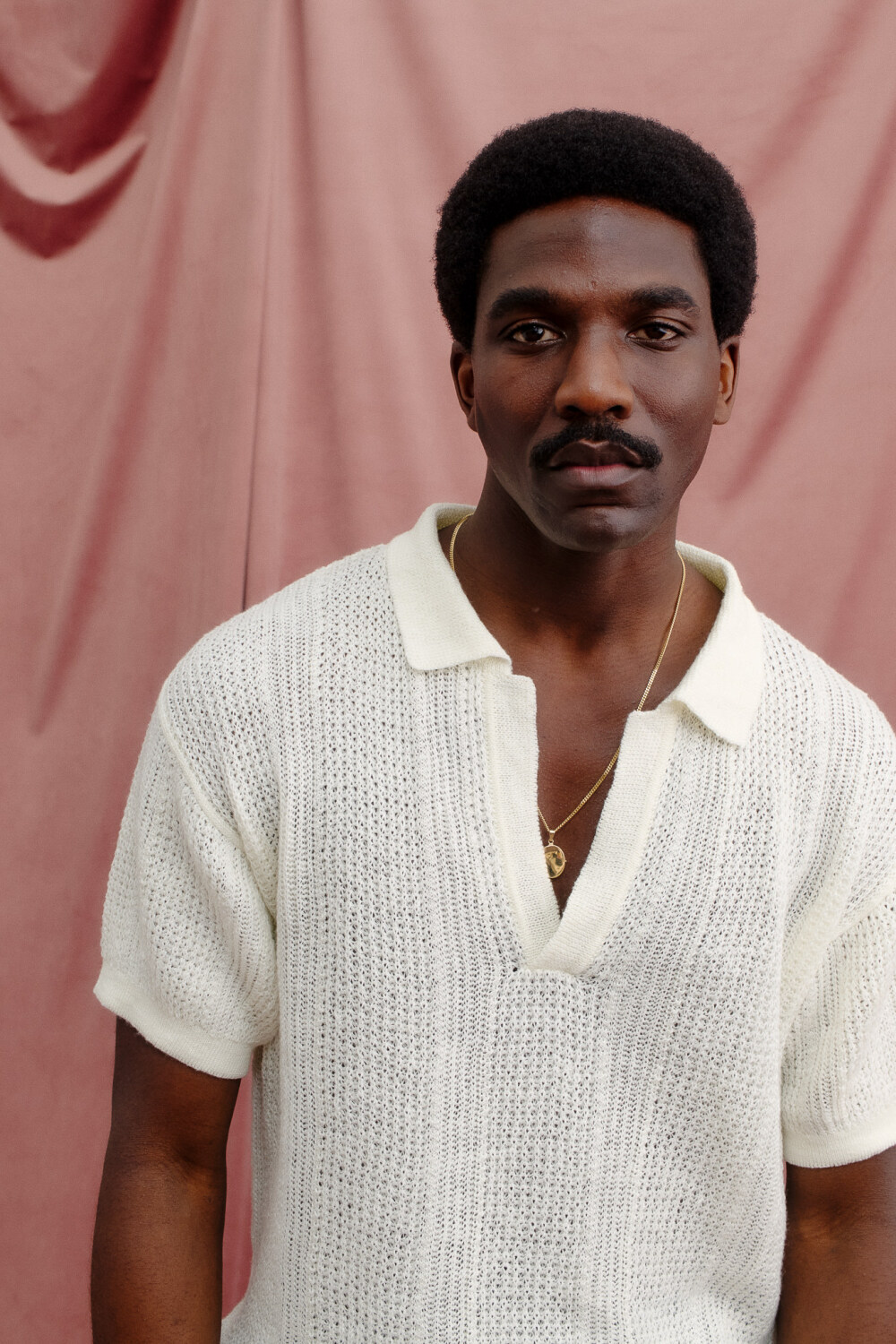

As the weather warms, I find myself reaching again for camp collar shirts. Short-sleeved versions look especially good with fuller-cut shorts, the kind that don’t cling to your thighs or resemble chopped-off slim-fit chinos. This season, Imogene + Willie, Monitaly, and J.Crew are offering excellent options with that boxy, almost Patagonia Baggies-like silhouette, where the leg hovers around your thigh like a hula hoop. Long-sleeved camp shirts feel a little more refined, like something a character in The Talented Mr. Ripley would wear. They look especially good in white linen, though that can sometimes verge on sheer. I usually reach for solid colors or patterns instead, depending on whether I’m dressing up for dinner or just running out for groceries. Solids feel more polished; patterns more relaxed and expressive. I especially like them in cotton, linen, or Tencel, a slippery material that feels like silk but doesn’t require special upkeep.

Camp collar shirts pair naturally with jewelry, where a necklace can serve a similar function as a necktie by adding visual interest and drawing the viewer’s eye upward. Lately, I’ve been admiring Santos de Cartier chains—recently seen on Colman Domingo and The Armoury’s Alan See—although the prices are very dear. Vintage Cartier pieces are even better, with shaped links that feel more sculptural, although they’re difficult to find and priced accordingly. For something more accessible, consider a simple 3mm diamond-cut rope or Franco chain—both understated but with faceted sides that catch the light. Front General Store and Reliquary are also worth checking for vintage pieces.

Options: Portuguese Flannel is great for camp collar shirts, as they do them a ton of fabrics. You can find them at No Man Walks Alone, Mr. Porter, and Stag Provisions. Also check out G. Inglese, ts(s), Seuvas, Engineered Garments, Bryceland’s, Todd Snyder (the company is great for this sort of thing but I especially like this shirt), J. Crew, RRL, Frescobol Carioca, Story Mfg, Séfr, Indi + Ash, The Real McCoys, Attractions, Wynona (their Merino Belmondo shirt is getting restocked in different colors soon), The Armoury, The Anthology, Buck Mason, Róhe (big collar!), 11.11/ eleven eleven, Kardo, Kartik Research at Mr. Porter and SSENSE (fun bohemian brand), Stoffa, Bode, Venroy, Sun Surf, Percival, Wales Bonner, Mr. P (good value) and Abercrombie & Fitch on a budget. Remember that Post Romantic (an advertiser on this site) and Proper Cloth can also make custom shirts with a camp collar.

The Rumpled Cotton Suit

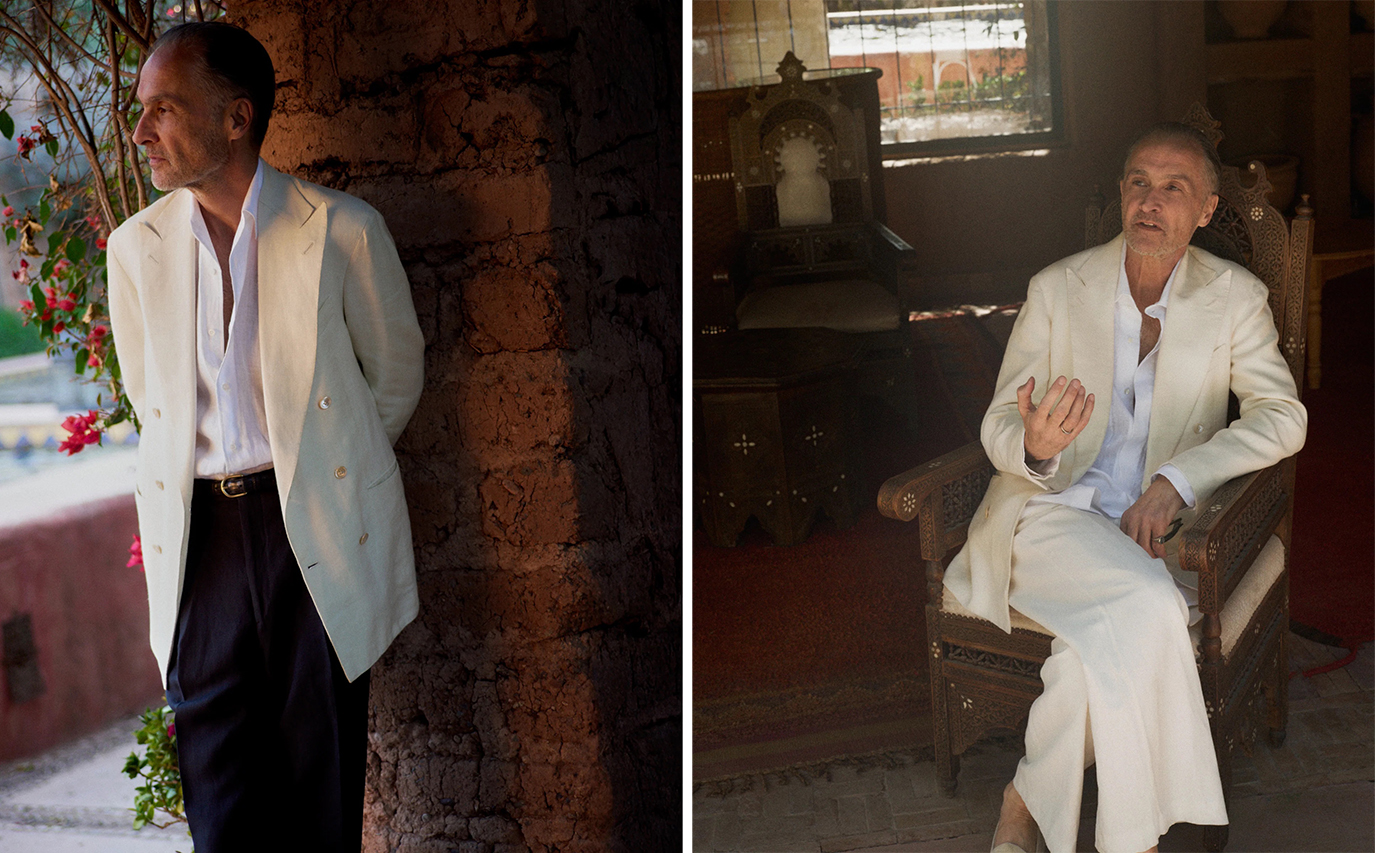

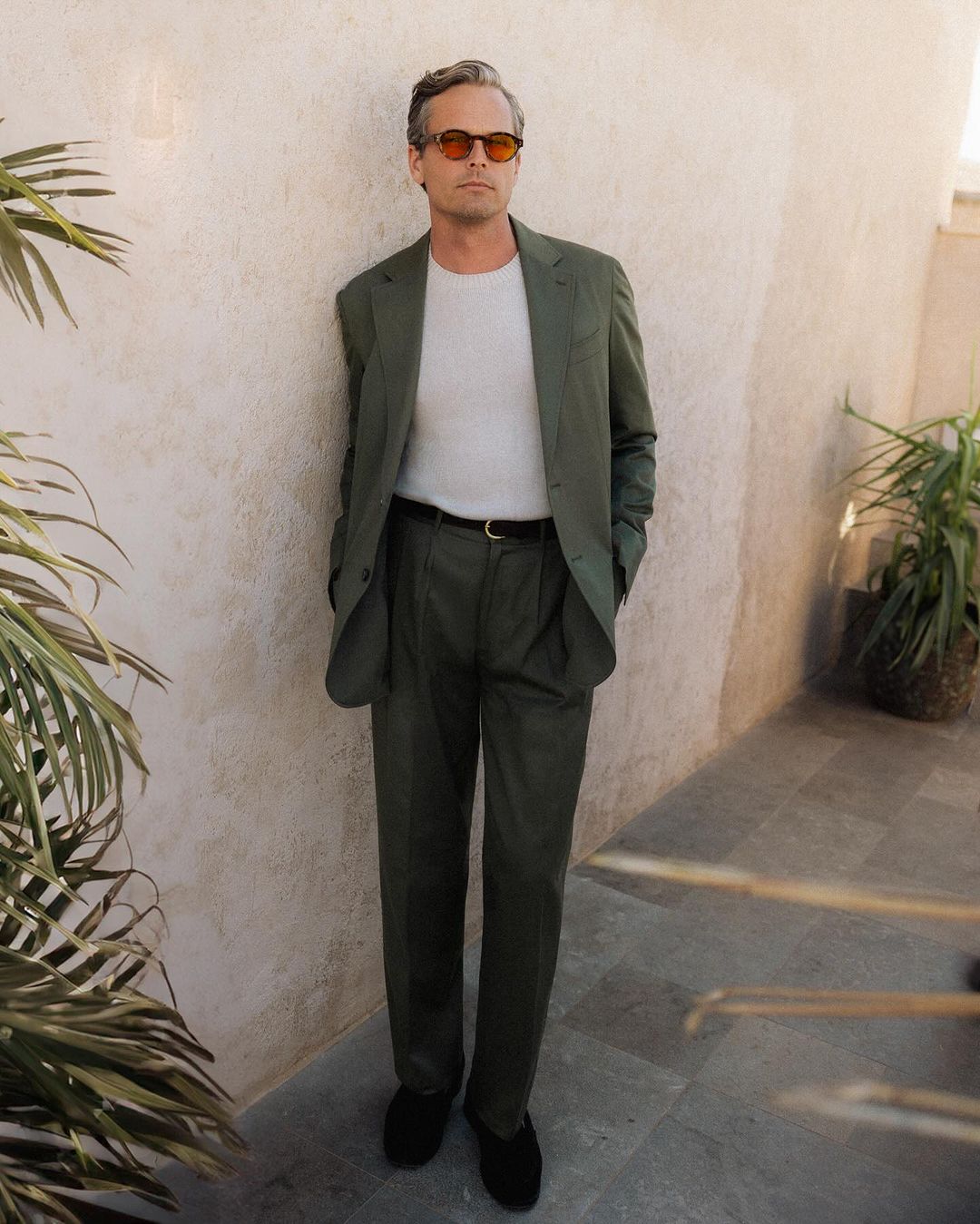

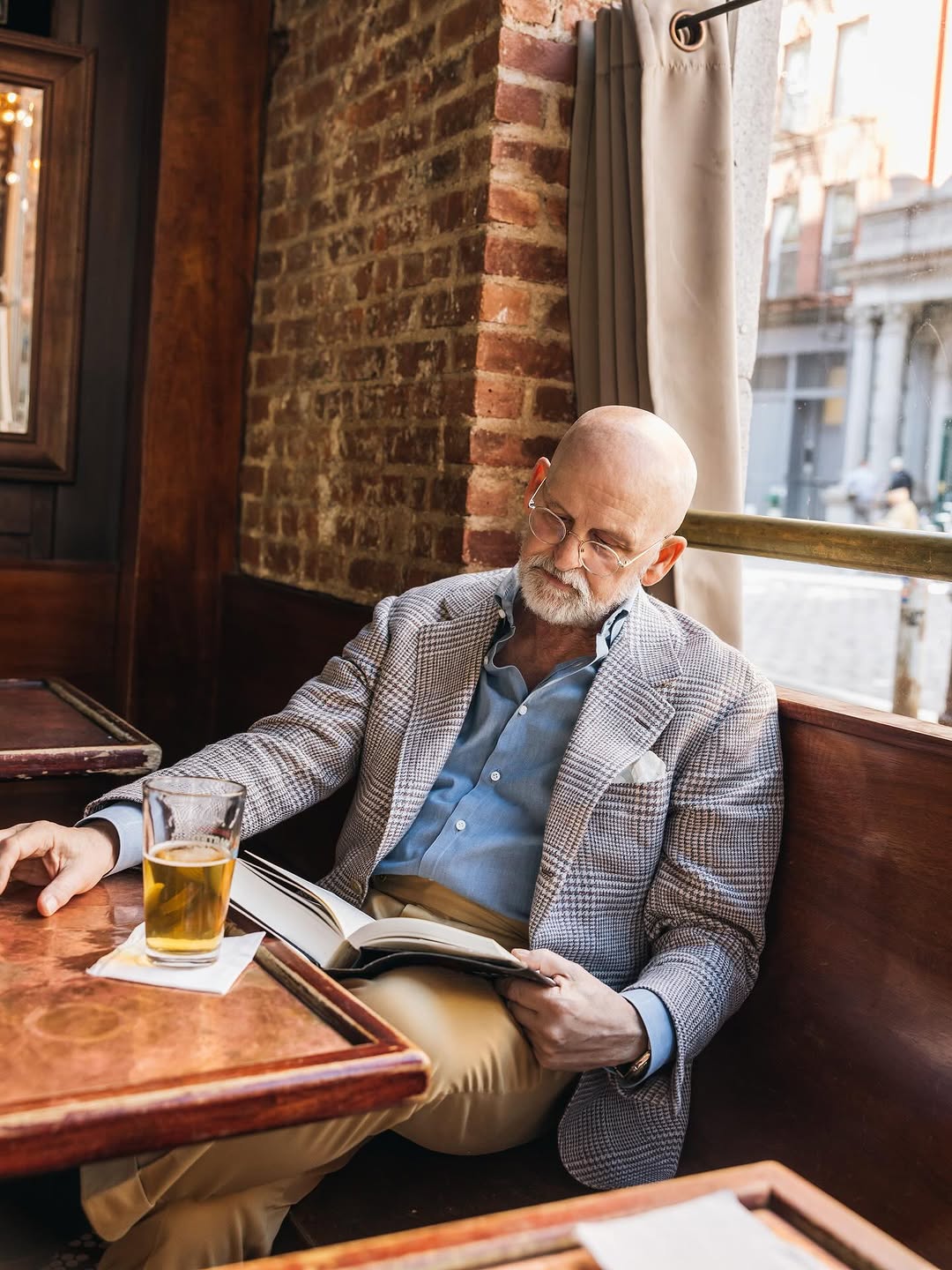

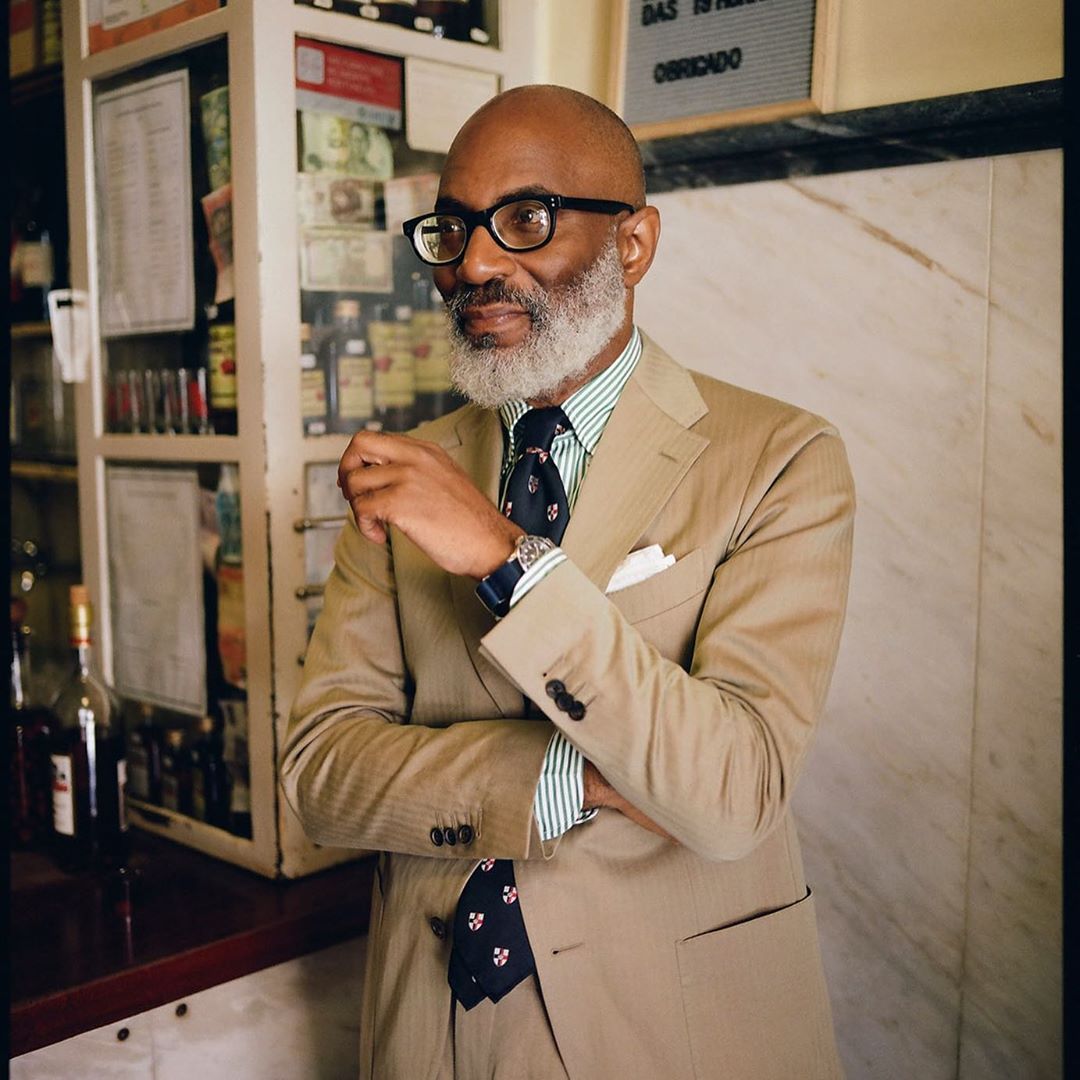

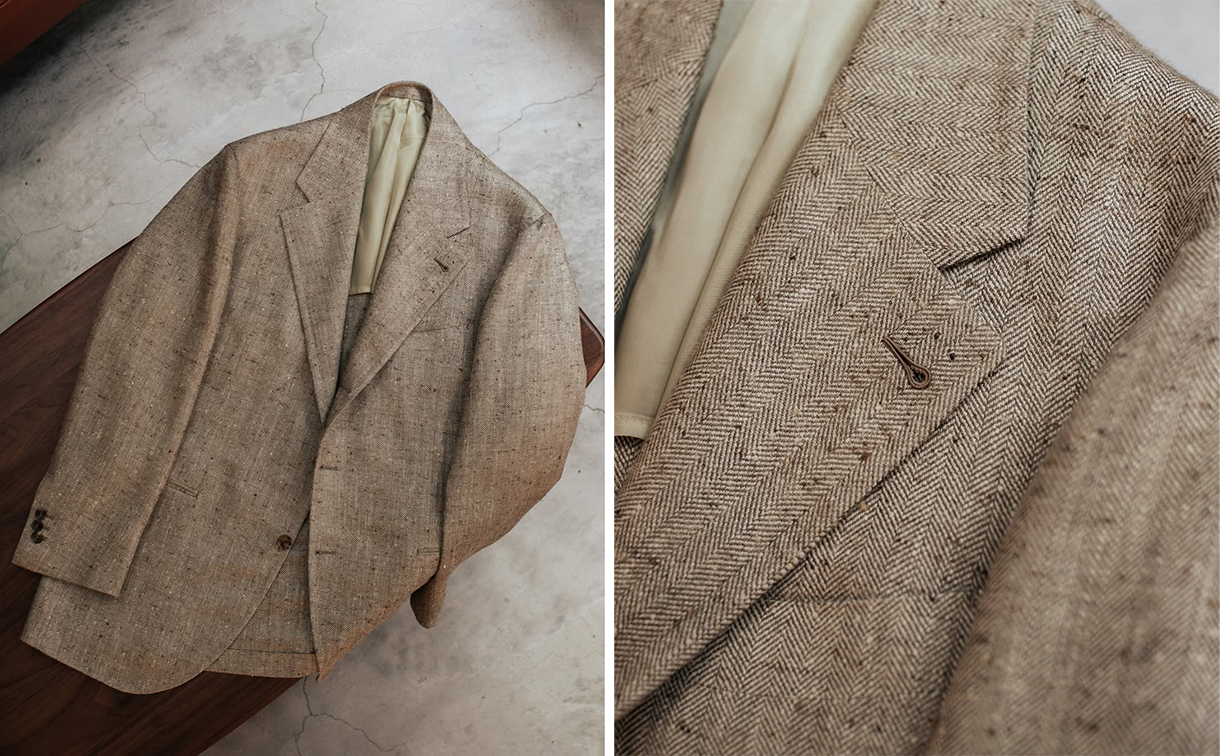

Nothing signals leisure quite like a casual suit. It’s too formal for places that don’t require a suit and too casual for settings that do, signaling to others that the wearer has no pressing obligations. A casual suit is the sort of thing you throw on with loafers and a knit shirt to browse bookstores, linger in cafés, or meet friends for dinner.

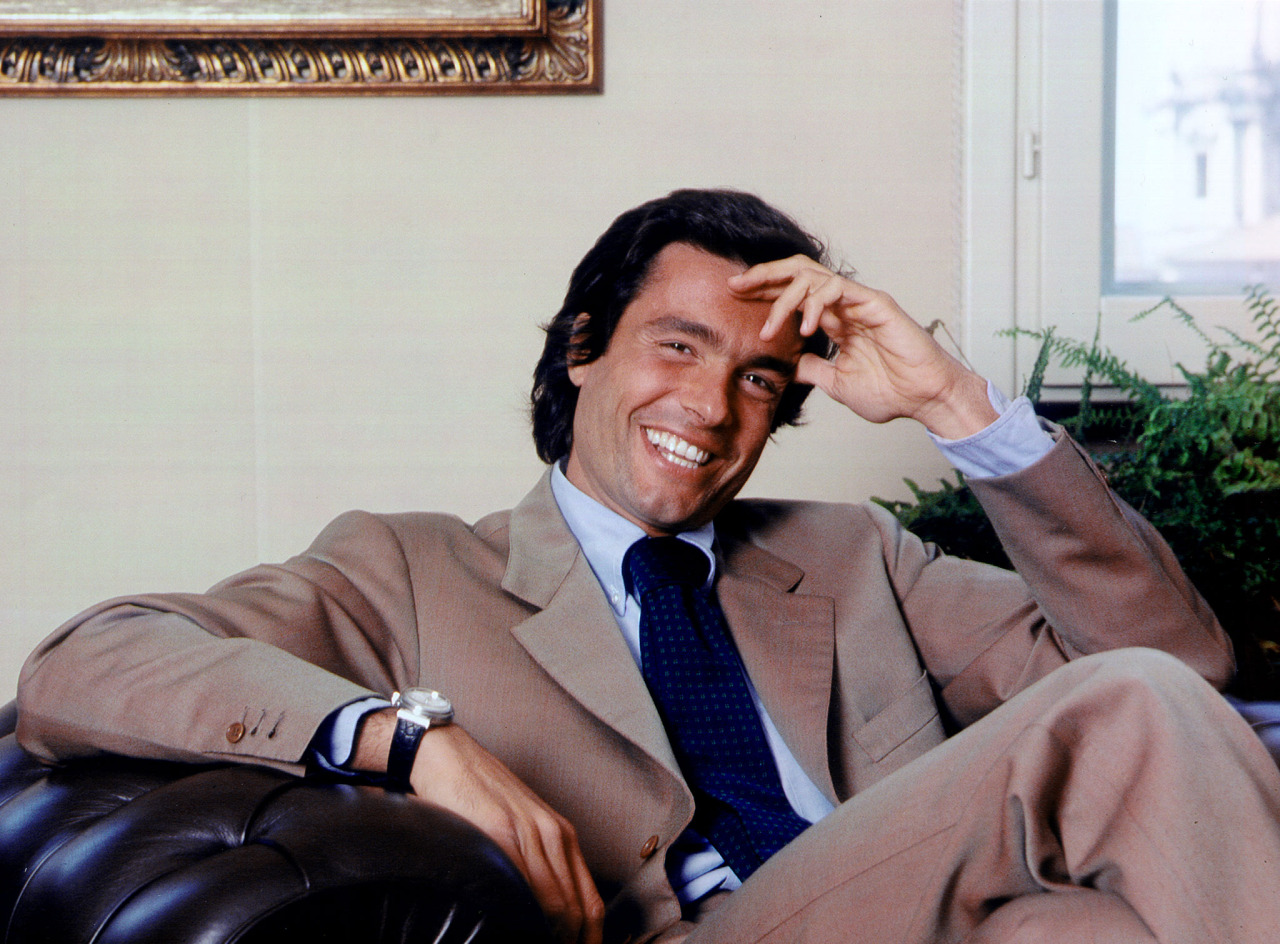

One of my favorites is from I Sarti Italiani: a single-breasted, notch-lapel, 3-roll-2 cut in the color of cremini mushrooms. It’s also (gasp!) a cotton-elastane blend. Cotton, lacking the natural crimp of animal hair, can wear a bit stiff. But with just two percent elastane—less than what you’ll find in a pair of Italian dress socks—you get a suit that moves more fluidly and wears more comfortably. The jacket can be dressed down with jeans; the trousers double nicely as chinos. Worn together, they pair easily with OCBDs or T-shirts, and finish well with penny loafers or plain white canvas sneakers.

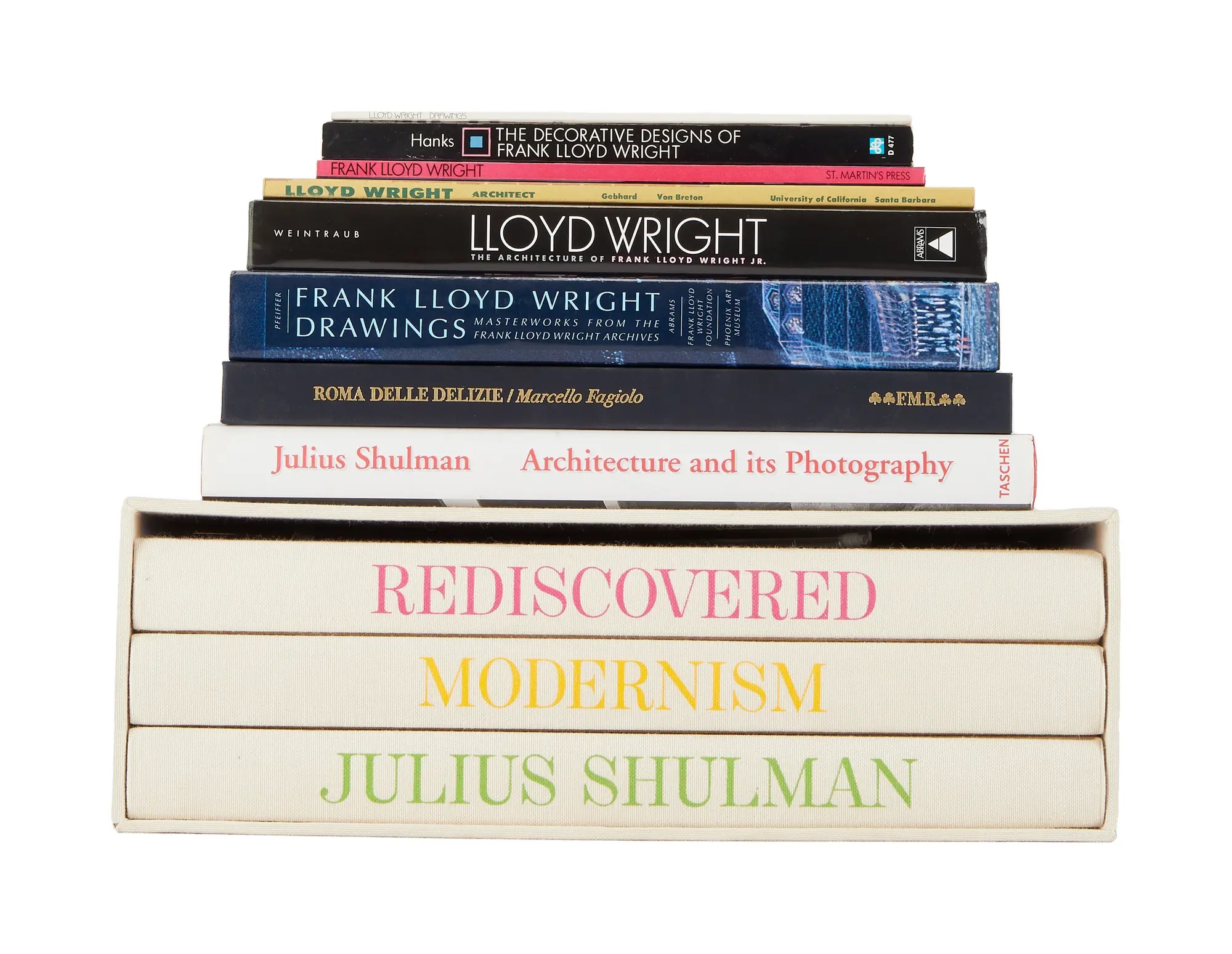

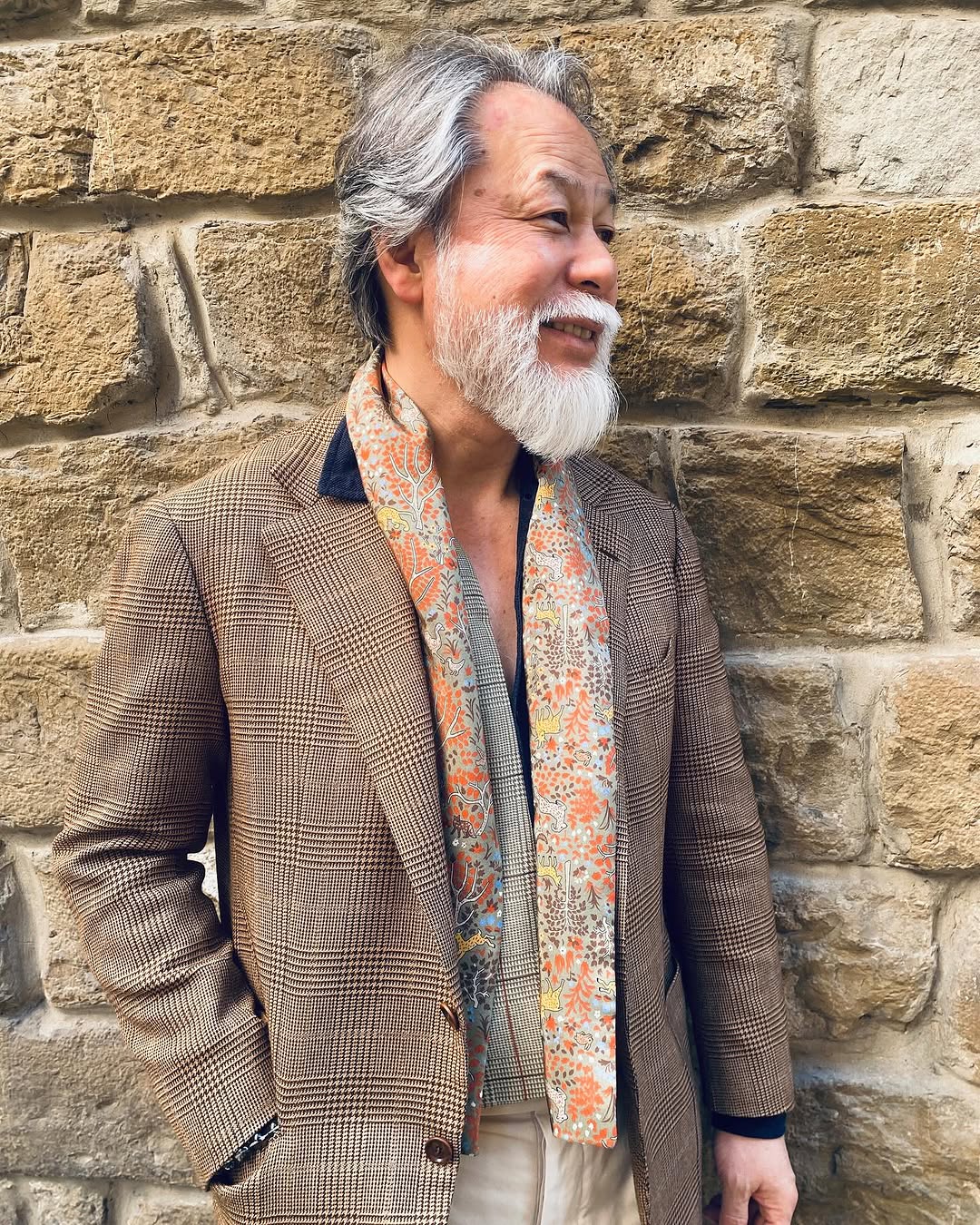

That said, pure cotton can be beautiful in its own right. Like a good pair of jeans, it softens and rumples with wear, developing a lived-in texture that makes casual tailoring feel more like an extension of yourself than a costume. Mark Cho, co-founder of The Armoury, is also a fan. “If you like denim, chinos, oxford cloth shirts, polos, chore coats, and Barbour, then you will like cotton suits,” he told me. “They are the apex of relaxed style. They’re enjoyable for everyday use and very low maintenance, looking better and better with wrinkles and wear.” When buying your first one, stick to light, earthy colors such as taupe, sand, stone, or olive. Cotton fades in patchy ways, which can look less charming in darker colors like navy.

Options: The Armoury, Drake’s, Spier & Mackay, Suitsupply, Buck Mason, and Todd Snyder. If you’re ordering custom, check out Zegna’s Winter Cottons book

The Workhorse Chambray Shirt

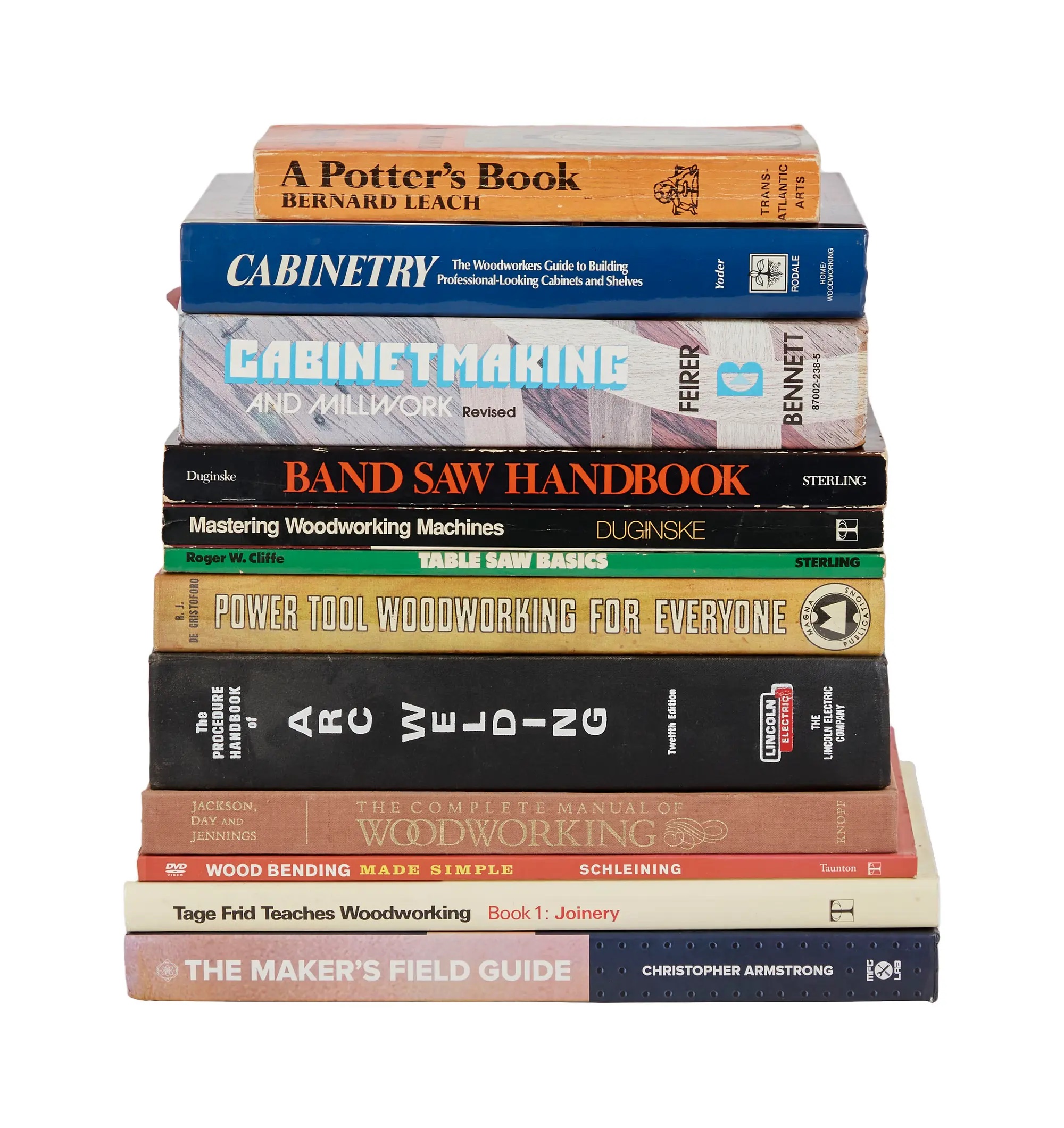

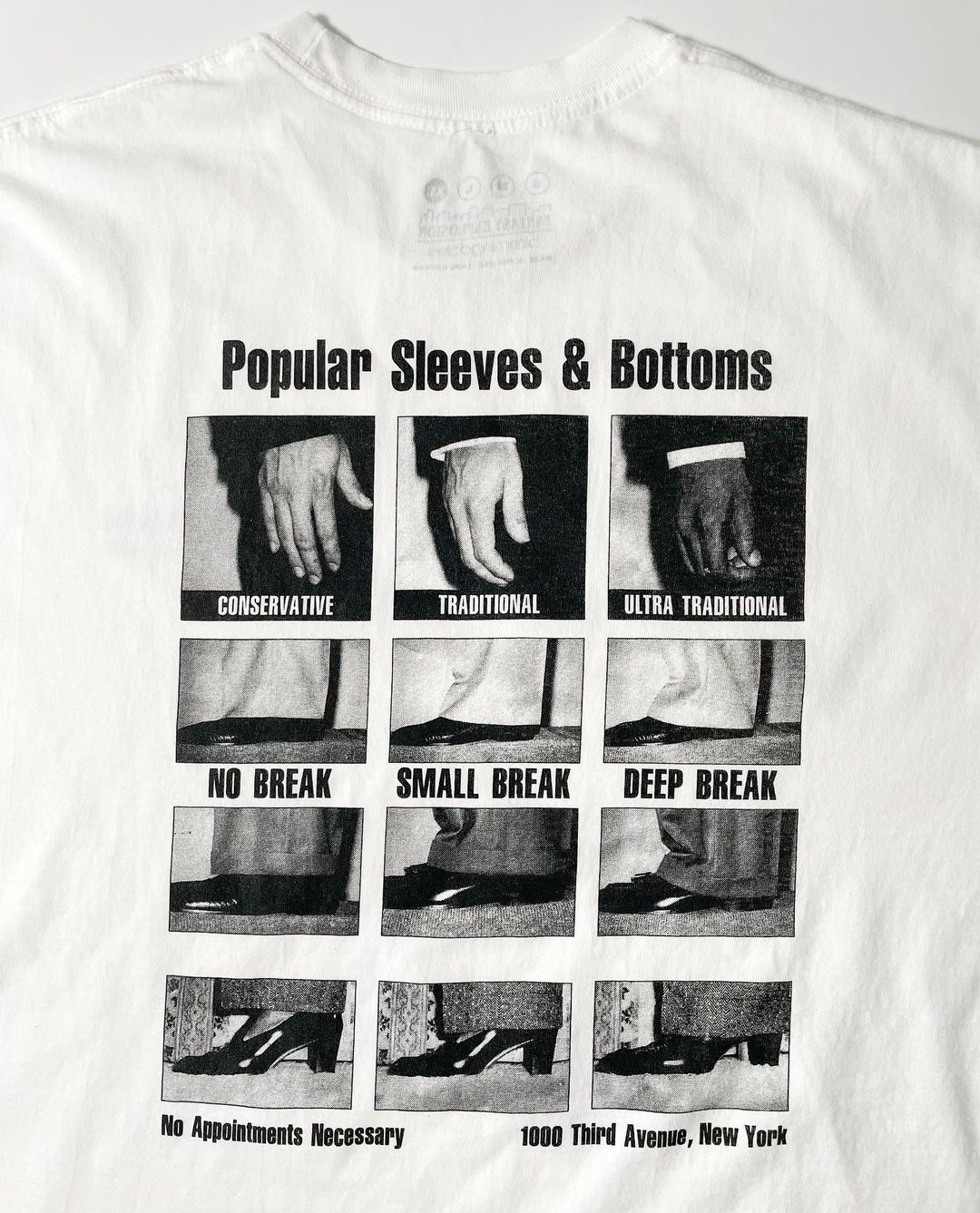

In the early 20th century, when work was strictly divided by gender, a small army of women carved out careers by teaching Americans the science behind cooking, cleaning, and sewing. Some found positions within the USDA’s Bureau of Home Economics, where they wrote and published practical guides on how to buy and care for quality clothing. One such document, a 1939 farmer’s bulletin published near the tail end of the Great Depression, featured advice from a junior home economics specialist named Margaret Smith. Writing on how to choose reliable work shirts, she noted: “For outdoor work in mild weather, choose a material such as chambray, which is durable, firm enough to prevent sunburn, yet lightweight enough to admit air and be fairly cool.”

Before chambray shirts turned up in expensive Fifth Avenue boutiques, they belonged to men whose livelihood depended on their hands. During America’s Industrial Revolution, chambray’s plain weave and lightweight nature offered a rare compromise: tough enough to withstand physical labor in factories and on farms, yet light enough to prevent suffocation in the punishing heat. Textile mills across the U.S. began producing bolts of indigo chambray, and workwear companies like Heracles and Big Yank cut them into boxy, utilitarian shirts built for machinists, miners, and field hands who needed room for comfortable movement.

By the 1930s, the chambray work shirt had become a uniform of the American working class. It was the blue chambray shirt, after all, that Upton Sinclair helped enshrine as a symbol of class distinction: “blue collar” came to represent manual trades, while “white collar” referred to the managerial class. Typically made with double- or triple-needle seams, cat-eye buttons, and dual chest pockets, chambray shirts were worn under coveralls in Midwestern foundries and tucked into jeans on California farms. It’s a shirt that came to represent American grit and honesty. When Paul Newman played a defiant inmate in Cool Hand Luke, released just as antiwar protests were erupting across the country, he wore blue chambray.

I’ve cycled through a handful of chambray shirts over the years—RRL, Engineered Garments, and J. Crew among the many. My favorite is from the New York-based label Chimala, designed by the press-shy Noriko Machida. Chimala’s menswear has the sensibility of womenswear inspired by menswear. It is thoughtfully designed and expertly crafted by Japanese artisans who can replicate the wear and fading of vintage garments in a way that feels authentic rather than costumey. My old shirt had sun-faded fabric and patched-up holes as if someone had pulled it from a Parisian flea market rather than a showroom. Unfortunately, I’ve since gone up a size, and what was once a slim fit now feels more like a straitjacket. The new season’s version is nice, but not exactly the same as what I bought fifteen years ago.

I recently replaced it with a special order from Bryceland’s, inspired by something I saw on Permanent Style. The design combines the unique teardrop pockets from Bryceland’s work shirt with the longer collar points of their USN chambray, which helps it sit more cleanly under a tailored jacket. I went with the pure cotton chambray rather than the cotton-linen blend, although the latter does a better job of wicking moisture from the skin. It lacks the runoff chain stitching you’d find on some of the more obsessive vintage repros from brands like The Real McCoys, but the mother-of-pearl buttons—still cat-eye in shape—give it a slightly dressier feel that works better with tailoring. For guys who move between sport coats and workwear, it might be the perfect option.

I think chambray shirts look especially good in the summertime with off-white jeans (or cream-colored painter pants, if you want to avoid the preppy connotations). They also look great with olive fatigues, tan carpenter pants, and black jeans. Seiji McCarthy, a bespoke shoemaker based in Tokyo, tells me he considers his Bryceland’s chambray as a Swiss Army Knife. “On a hot day, you can leave it unbuttoned over a T-shirt to give you some breathable cover from the sun,” he says. “On a cool day, you can tuck it in and wear a chore coat on top, or for a more elegant look, wear it underneath a cream cashmere sweater with corduroys and an odd jacket. The shirt is versatile because the fabric is lighter and softer than oxford cloth, while the blue threads fade to a color that’s very easy to coordinate. My original Bryceland’s chambray is so beaten in and broken down that it serves as an ideal companion to the dusty coveralls I wear at the workshop. It’s hard to think of another item of clothing that gets so much use and provides so many opportunities for wear.”

Options: Bryceland’s, RRL, Engineered Garments, J. Crew, Chimala, The Real McCoys, Buzz Rickson, Warehouse, Seuvas, Drake’s, Todd Snyder, Orslow, Ordinary Fits, Neighborhood, Imogene + Willie, Buck Mason, Eastman, Indi + Ash, Black Sign, and The Anthology. Again, Proper Cloth is also a great source for made-to-measure shirts. They have a wide range of chambray fabrics.

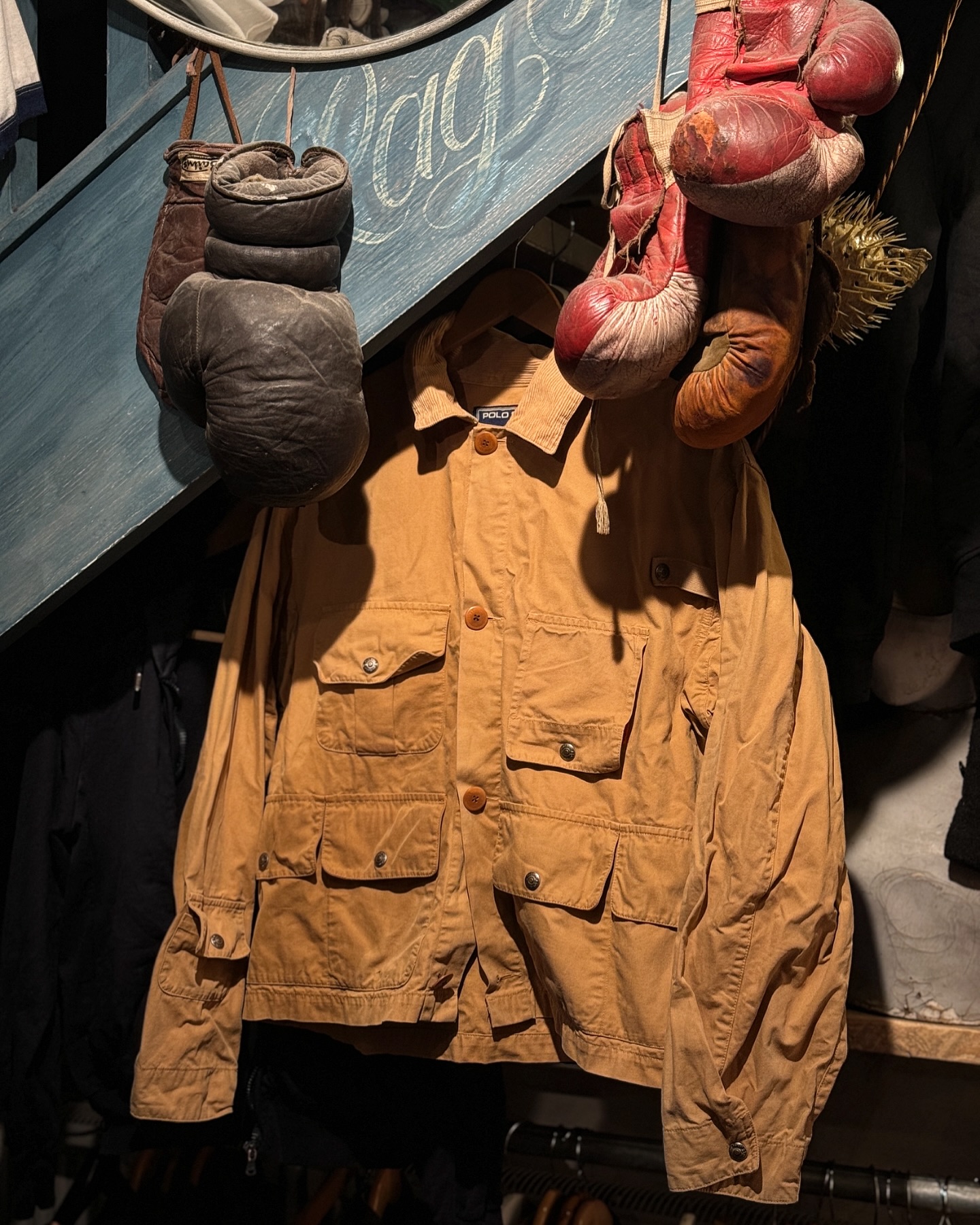

The Fishing Jacket

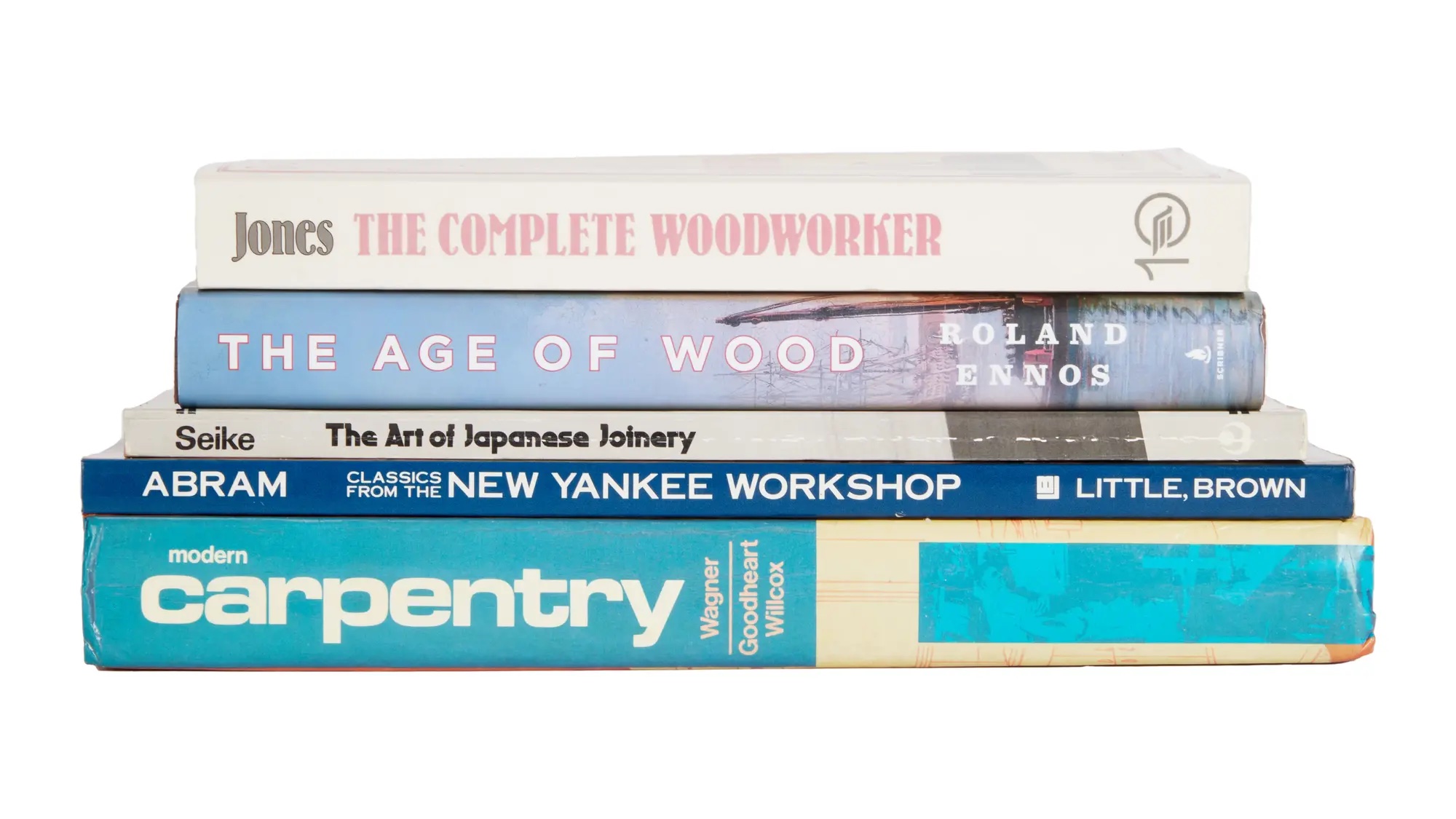

Izaak Walton’s enduring pastoral treatise, The Compleat Angler, offers detailed instruction on how to catch trout, perch, carp, umber, pike, salmon, tench, gudgeon, grayling, bream, barbel, and even the humble bleak. But it would not have become one of the most reprinted works in the English language if it were only about fishing. To understand it, you have to consider the book’s context. First published in 1653, The Compleat Angler appeared just four years after the execution of King Charles I and at the height of Puritan rule under Oliver Cromwell. Walton, an Anglican and Royalist, found himself politically and spiritually adrift. Having made his fortune as a linen draper, he withdrew to the countryside near Stafford, where he devoted his energy to writing about the good life, far from the noise of the English Civil War.

Structured as a series of dialogues between the reflective Piscator and his more impetuous companion Venator, The Compleat Angler blends practical fishing advice with pastoral reverie and literary ornament. Their conversations meander through riverside landscapes and rustic inns, offering guidance on bait, tackle, and fish habits while often pausing for meditations on humility and friendship. “Good company and good discourse are the very sinews of virtue,” Piscator observes at one point, a sentiment that reflects the book’s broader vision of moral and social life. To be a gentleman, he says elsewhere, is to be “learned and humble, valiant and inoffensive, vertuous, and communicable.” Angling becomes a metaphor for a contemplative life lived in quiet harmony with nature, removed from both fanatical zealotry and idle worldliness. What endures is not just instruction on how to catch trout but a vision of how to live; the book closes with the exhortation to “study to be quiet.” Piscator contrasts the angler’s measured joy and simplicity with the restless discontent of “money-getting men” and “poor-rich men,” who, despite their abundance, remain spiritually exhausted.

In one of my favorite passages, Piscator urges his companion to take stock of what truly matters: the simple pleasure of eating, drinking, laughing, angling, singing, and sleeping soundly, then rising the next day to do it all again. As they walk together in the cool shade of a honeysuckle hedge, he reflects on the miseries that others endure but from which they have been spared—gout, broken limbs, and, above all, the burden of a tormented conscience. “Let not us repine,” Pastor encourages, “or so much as think the gifts of God unequally dealt, if we see another abound with riches; when, as God knows, the cares that are the keys that keep those riches, hang often so heavily at the rich man’s girdle, that they clog him with weary days, and restless nights, even when others sleep quietly. We see but the outside of the rich man’s happiness: few consider him to be like the silkworm, that, when she seems to play, is, at the very same time, spinning her own bowels, and consuming herself. And this many rich men do; loading themselves with corroding cares, to keep what they have, probably, unconscionably got. Let us, therefore, be thankful for health and a competence, and above all, for a quiet conscience.”

Even for men like me, who have no desire to bait a hook or cast a rod, there’s something beautiful in the way fishing cultivates patience, contentment, and the ability to find joy in stillness. In Walton’s time, these were virtues that stood against the noise of ambition and the frenzy of political strife—just as they resist the digital churn that now arrives nightly via push notifications. The sport has also, it must be said, given us some excellent outerwear. When Andy Warhol arrived in Beijing in 1982 as part of the first wave of Americans allowed into China after the normalization of U.S.–China relations, he wore a soft-shouldered blazer with an oxford cloth button-down, a rep striped tie, Levi’s jeans, and cowboy boots. But the standout piece was a distinctive, multi-pocketed Italian jacket, originally designed for hauling photography equipment but looked awfully like the kind of jackets men wear to hold fishing lures. Since then, that jacket has been endlessly reproduced by brands such as The Real McCoys, Name, and Renoma Archive Club. My favorite in this category is Kaptain Sunshine, although you’ll have to scour second-hand markets for old seasons’ versions.

Countless brands, from Ralph Lauren to Beams Plus, have taken inspiration from fishing jackets originally designed for utility. With their chaotic sprawl of pockets and oddball proportions, they make for surprisingly good spring outerwear. Typically cut short and made from lightweight fabrics, they don’t suffocate in the heat but still add texture and shape, especially that cropped silhouette that’s been popular in recent years. Plus, they show you don’t take yourself too seriously. I particularly like Brut’s reworked versions, along with vintage fishing jackets from the now-defunct mid-century American label Ideal. They go naturally with chambray shirts, beat-up jeans, and Russell Moccasin’s fishing oxfords.

Natalie Compton, a travel journalist for The Washington Post, recently wrote about how a fishing vest can serve as a substitute for the carry-on bag that now comes with a fee. “Tbh you look very chic,” fashion critic Rachel Tashjian replied in the Instagram comments (a style co-sign, in my book). But away from rivers or airports, these jackets are, admittedly, completely impractical. The extra storage doesn’t offer much convenience; it mostly just makes finding your wallet more complicated. Still, in that slow, meditative ritual of checking each pocket, you might buy yourself a few precious seconds at the end of dinner—just enough time to avoid picking up the check. In that way, the jacket practically pays for itself.

Options: Kaptain Sunshine (if you can find it), The Real McCoys, vintage Ideal, Monitaly, South2 West8, Woolrich Outdoor Label Designed in Japan, Ralph Lauren, Barbour Spey, Barbour Reworked, Barbour x To Ki To, Brut rain cropped jacket, Brut wader jacket, and LL Bean

The Looser Jeans

Brands often become diluted as they expand, primarily because they need to sell more units to cover the rising cost of retail space. However, in recent years, Buck Mason has quietly transformed from a purveyor of solid, if forgettable, basics into a label that gets regularly mentioned in menswear circles. Over the past year alone, they’ve partnered with in-the-know brands, such as J. Press, Bryceland’s, and J. Mueser. Their collaboration with Lee featured some items celebrating Tokyo’s “Yokohama Twistin’ Club”—a nod to the Japanese rockabilly dance crew beloved by menswear nerds for their pompadours, cuffed selvedge jeans, and devotion to 1950s Americana. And somehow, amid all this, they’ve continued opening stores while also reviving a 150-year-old knitting mill in Mohnton, Pennsylvania.

On some things, Buck Mason also seems slightly ahead of the curve. I recently picked up a pair of their “Full Saddle” jeans, which are made in the USA, cut from Kaihara denim, and feature a silhouette that I think a lot of guys are looking for right now: a high-rise with a straight, comfortable leg that’s neither JNCO baggy nor 2010s-menswear slim. There are a few small things you could nitpick—the jeans are described as “loomstate,” even though they’ve been rinsed, which technically means the fabric is no longer in its loomstate condition. Still, the fabric has a slightly uneven character that makes it more interesting than your standard Cone Mills denim, making it more promising for interesting fades. The cut is ideal for guys who want to shift away from the slim silhouettes that have dominated menswear for the last twenty years but prefer a classic look. Plus, the cut comes in Army chino form.

On the other side of the style spectrum, I also recently picked up a pair of Levi’s 517s, the company’s 1969 bootcut originally made from resin-coated Sta-Prest cotton designed to hold a permanent crease. They’re slim through the thigh, flat through the seat, and flare out around the ankle, giving them that distinctive silhouette Levi’s once marketed as “full from the knee for the boot.” I may be spoiled by Bryceland’s P13 cargo pants, which are so voluminous they could catch the wind and sail themselves down San Francisco’s Market Street. The Levi’s 517 “Saddleman” jeans—a precursor to their 646 Bell Bottoms—have a low rise that tends to slip off my hips. I find them a bit uncomfortable, but Ethan Newton of Bryceland’s says they’re the kind of thing you wear when you want to feel sexy (he owns a vintage pair made in the USA). “Think of that iconic photo of Led Zeppelin,“ he gently encouraged over the phone. “They’re the kind of thing you wear with boots and leather jackets.” He’s such a fan that his store released a similar model based on 1970s Lees, often styled with their Bowhill & Elliott Grecian slippers. I’m still undecided about my Levi’s, but at $98—even less for the non-premium version—they’re not a significant risk. I particularly like how Willy wears them.

Options: For slightly fuller cut jeans, check Buck Mason, Gustin 1968, Samurai S3100VX, Boncura, Levi’s 1947 501s, The Armoury, Rubato, Imogene + Willie Hank, and Blackhorse Lane NW1. For bootcut jeans, check Bryceland’s, Todd Snyder, Husbands, Levi’s, Lee, and Wrangler Cowboy Cut and Wranchers (note, the Wranchers are polyester). Peter also picked up a pair of vintage Lee bootcut jeans on eBay. He recommends looking for a “made in USA” label and double check sizing, as the tagged waist size may no longer be accurate given the shrinkage over the years.

The French Grocery Bag

In the opening of Virginia Woolf’s famous novel about upper-class life in post–First World War England, protagonist Clarissa Dalloway sets off to buy flowers for her dinner party. “I love walking in London,“ she tells her friend Hugh. “Really, it’s better than walking in the country.“ Dalloway is no model of contentment; her inner life is shaped by private uncertainties and the lingering ache of time passing. Yet, in that quotidian act of walking through the city, she finds a moment of joy, even a sense of purpose. I think about that often. One of my daily pleasures is walking to buy groceries—sometimes just the missing ingredients for dinner or a handful of ripe nectarines, apricots, or plums for a snack. It’s not just an errand but a ritual: a way to feel present in a neighborhood and enjoy some contemplative stillness (or leisure, as Pieper put it). The older I get, the more I realize how much I value living in a walkable neighborhood, not only for convenience but also for these small experiences that turn chores into something close to a blessing.

For that reason, I’ve been into open-netted French market bags. Originally crafted by Norman fishermen and later adopted by their wives for market runs, these bags—filets à provisions—rose to popularity across France in the 1920s. They were small and mighty, able to haul heavy loads much like the nets that once held fish from the sea. Variations spread through Eastern Europe and the Soviet bloc. In East Germany, they were made from strong waxed cotton called Eisengarn and tucked into pockets “just in case.“ In Russia, they became known as avoskas, from the word for “maybe,“ a reference to the Soviet habit of carrying a net bag everywhere in case something unexpectedly appeared on the shelves during shortages.

For a while, these open netted market bags were dismissed as dowdy or dated—too closely associated with frugal grandmothers, like tear-off lunar calendars or those plastic plaid laundry bags you see in Chinatown. But much like tweedy Balmacaan overcoats or Norwegian split-toes, it’s that association with an older, more elegant generation that makes them charming to me. They come in a wide range of colors, and while you could haul a full grocery run in one, I usually use mine to bring back just enough for a salad and maybe some fruit. In other words, just enough for a little walk to the grocery store. At $20, they’re an affordable way to feel fancy.

Options: Filt and Lemaire if you’re fancy